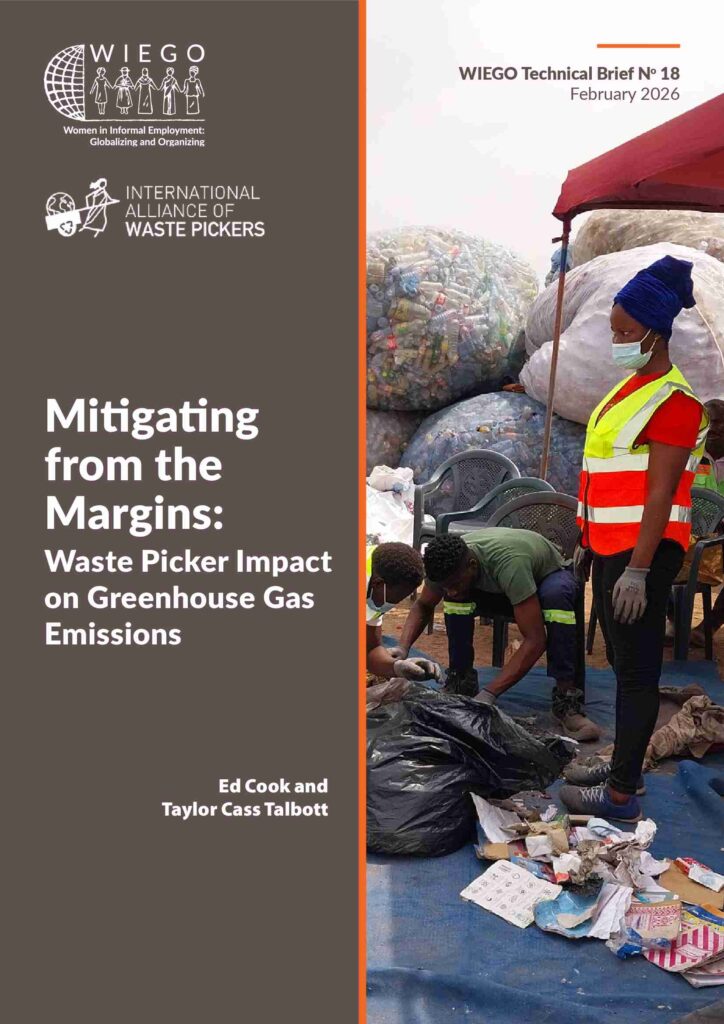

Waste pickers search for recyclables at the Kpone Landfill in Accra, Ghana. Photo credit: Dean Saffron

Who Are Waste Pickers?Millions of people worldwide make a living collecting, sorting, recycling and selling materials that someone else has thrown away. In some countries, waste pickers provide the only form of solid waste collection, providing widespread public benefits and achieving high recycling rates.

Waste pickers play a key role in urban economies and systems. Their work collecting recyclables from city streets, keeping public spaces clean and feeding the industries with recyclables comes at little cost to municipal budgets and industries. It is well established that waste pickers contribute to reducing carbon emissions. However, they often face low social status, deplorable living and working conditions, and little support from governments and industries. Policy interventions are needed to increase incomes; guarantee a living wage; ensure adequate (and implemented) standards of work health and safety; integrate waste pickers in adaptation plans, ensure freedom for workers from discrimination and ensure the right to organize collectively.

Just Recycling: The Social, Economic and Environmental Benefits of Working with Waste Pickers

Defining Waste Pickers

The term “waste picker” refers to individuals who collect reusable and recyclable materials (either segregated or mixed) from residential and commercial waste bins, large generators, dumpsites and public spaces to repurpose or direct these materials to recycling and earn their living.

At the First World Conference of Waste Pickers, held in Colombia in 2008, a provisional consensus was reached to use the generic term “waste picker” in English to supplant the derogatory term of “scavenger”. It was also recommended that, in specific contexts, the term preferred by the local waste picking community should be used. For example, in South Africa “reclaimers” and “bagerezi” are used. In the United States, “canners” is often used. Other languages have their own preferred terms: catadores in Portuguese, recicladores in Spanish.

While an international consensus is still to be reached among workers, activists, waste specialists and researchers, the term waste pickers has been put into use by WIEGO as a generic term. The International Alliance of Waste Pickers (IAWP) has an all-encompassing definition that includes several categories of workers, enabling networking across different contexts.

Waste pickers collect household or commercial/industrial waste. They may collect from private waste bins or dumpsters, along streets and waterways or in dumps and landfills. Some rummage in search of necessities; others collect and sell recyclables to middlemen or businesses. Some work in recycling warehouses or recycling plants owned by their cooperatives or associations (see basic categories of waste pickers for more).

What waste pickers have in common is that this work is their livelihood and often helps support their families.

Challenges & AdvancesStatistics on Waste Pickers

Reliable statistical data on waste pickers are difficult to produce. Employment data are collected through household surveys but many waste pickers live on the streets or on dump sites and therefore would not be included in the survey sample. Waste pickers are mobile and their work often varies seasonally. Further, waste pickers may avoid researchers, fearing information will be passed on to officials.

Many of the country reports in the WIEGO Statistical Brief series include data on waste pickers. However, for the reasons described above, the numbers are an underestimate. Still, the small percentage of waste pickers in the labour force often represents large numbers of workers. For example, according to the National Labour Survey in India, waste pickers were 1% of employment, but this is 2.2 million workers. The WIEGO Statistics Programme has responded to the need for better data on waste pickers by documenting efforts to collect data on waste pickers initiated by organizations of waste pickers.These include The Collection of Data on Waste Pickers in Colombia, 2012-2022, WIEGO Statistical Brief No. 35, and Statistics on Waste Pickers: A Case Studies Guide, WIEGO Statistical Brief No. 39. Importantly, organizations of waste pickers had a collaborative role in all phases of the data collection process.

Brazil’s statistics on waste pickers are in Waste Pickers in Brazil: A Statistical Profile, WIEGO Statistical Brief No. 29 (also available in Portuguese) and Statistics on Waste Pickers in Brazil, WIEGO Statistical Brief No. 2.

-

15 to 20 million

in the world work as informal waste pickers (this figure is estimated).

-

Over 281,000

people work as waste pickers (catadores) in Brazil.

-

Over 25,000

people work as waste pickers in Bogota, Colombia.

Additional Statistics on Waste Pickers

-

It is estimated that 15–20 million people in the world work as informal waste pickers.

The ILO report indicates that an estimated 4 million workers are formally employed in the waste management and recycling industry, which means that workers in informal employment make up the bulk of this industry.

-

Of the 281,000 waste pickers (catadores) in Brazil, most are men (70%), while women comprise 30%. Although the absolute number of waste pickers has increased in recent years, waste pickers account for between 0.1% and 0.4% of all workers in Brazil. Although this is a low share, these workers are responsible for high recycling rates in the country. Brazil recycles 97% of cans and 67% of cardboard.

-

In Bogota, Colombia, there are more than 25,000 waste pickers. Bogota has a registration system updated yearly that provides data on waste pickers – the RURO (Unified Registry of Waste Pickers of Bogota). This comprehensive database on waste pickers, their work and their social characteristics compiles data through a variety of sources including waste picker organizations and the Special Administrative Unit of Public Services in Bogota.

Waste Pickers’ Contributions

Waste pickers not only bring the benefits of collecting solid waste at source and separating recyclables, but they also improve land use, preserving and extending green areas, improving water courses and preventing floods. They facilitate innovative energy systems and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. While contributing to the economy, the environment and public health, waste pickers are creating their own livelihoods.

Waste picking provides crucial income for people and households. In Belo Horizonte, Brazil, waste pickers said their cooperatives create opportunities for people, sometimes “taking them off the streets”.

Waste pickers provide reusable materials to other enterprises. In Pune, India, they collect organic matter for composting and biogas. In Belo Horizonte, Brazil, and Nakuru, Kenya, material is sold to artists and other groups to work with.

Many waste pickers sell to buyers, who then sell the material for a profit. Waste pickers also pay private carriers and transport drivers.

When organized and formally integrated into recycling systems, waste pickers increase their contribution to environmental protection. WIEGO’s Reducing Waste for Coastal Cities project built the capacity of workers’ organizations to improve their contribution in curbing ocean waste pollution.

By gathering garbage from public spaces, waste pickers contribute to cleanliness and help beautify the city. Waste pickers divert a significant quantity of materials from the waste stream. A 2020 report estimates that waste pickers collect 58% of plastics, thus contributing significantly to supplying the value chain and avoiding plastic pollution.

Recycling is one of the cheapest, fastest ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, yet privatized incineration increasingly displaces waste pickers around the world.

Reuse and recycling of materials decreases the amount of virgin materials needed for production, conserving natural resources and energy while reducing air and water pollution.

For a full discussion, see Urban Informal Workers & The Green Economy.

Driving Forces & Working Conditions

Waste picking is often a family enterprise but in some contexts, such as in Latin America, waste pickers have organized their work to be performed collectively in cooperatives.

Waste picking is highly responsive to market-driven conditions for recyclables.It offers flexible working hours – especially important for women. While it is usually easily learned and requires no education, the move to circular economies is increasingly requiring new skills. For many of the world’s poorest people, waste picking is one of the only livelihood options.

Waste workers are often subject to social stigma, face poor working conditions and are frequently harassed. Climate emergency has further exacerbated social, economic and spatial inequalities. Also, policy and investment responses to climate change often negatively impact the lives and livelihoods of workers in informal employment. In response is the call for a Just Transition that ensures the shift to a more environmentally sustainable economy is also economically sustainable.

-

Access to waste and privatization of waste are key issues that impact waste pickers’ livelihoods. At the First Global Strategic Workshop of Waste Pickers in Pune, India, in 2012, waste picker representatives from 22 countries identified privatization of access to waste as the biggest common threat to waste pickers’ livelihoods.

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) has threatened workers’ access to recyclables in several places. WIEGO has supported workers’ organizations in documenting different systems of EPR across the world and advocating that governments ensure the implementation of mandatory inclusive EPR policies.

-

Waste pickers’ earnings vary widely between regions, by the type of work they do, and for women and men. In Belo Horizonte, Brazil, where waste pickers are recognized and supported by governments and organized into strong cooperatives, waste pickers appear to have higher incomes than other workers in informal employment. By contrast, waste pickers in Nakuru, Kenya, subsist on meagre returns.

Men consistently earn more than women waste pickers, in particular among non-organized workers. In cooperative settings, the gap is less pronounced.

Waste pickers’ earnings are affected by market-driven prices for recyclables. Waste pickers require adequate space for sorting and storing collected materials until they can fetch a higher price.

The current cost-of-living crisis in many parts of the world hits waste pickers hard. In the 2008/09 global economic crisis, research by WIEGO and its Inclusive Cities partners found the crisis caused a marked drop in the demand for and price of waste. At the same time, many more newly unemployed people turned to waste picking to earn a living.

Within value chains, waste pickers are in a disadvantaged position. They often have difficulty negotiating prices and maintain exploitative relations with buyers.

Waste pickers provide recyclable materials to formal enterprises. In several countries, they have created cooperatives, which give them a political voice and also better bargaining power with middlemen. Collectives have engaged with large corporations to press towards implementation of social responsibility programs and safeguards.

For background, see The Urban Informal Workforce: Waste Pickers/Recyclers.

-

Social stigmatization compounds waste pickers’ difficulties. Most waste pickers have low levels of formal education and in many places the work is done by disadvantaged groups. For example, in Pune, India, waste picking remains confined to the Scheduled Castes. In many cities around the world, migrants with few other employment options take up this work.

For waste pickers, harassment is a part of daily life. Treated as nuisances by authorities and with disdain by the public, waste pickers are usually ignored within public policy processes and are sometimes even arrested or assaulted. They face exploitation and intimidation by middlemen. Interviews with waste pickers, observation of their work and visits to a dozen dumpsites in six Latin American countries – conducted as part of WIEGO’s Waste Pickers and Human Rights project and summarized in this report (in Spanish) – painted a picture of working conditions so poor that they amounted to human rights violations. A toolkit (in Spanish) has been developed for waste pickers to understand their rights and how to stand up for them.

Waste pickers’ organizations are a key force in counteracting this social and legal exclusion.

-

Women waste pickers typically earn less than men and often face other forms of inequality. The Latin American Waste Pickers’ Network (Red Lacre), the National Movement of Waste Pickers in Brazil (MNCR), and WIEGO created a project about gender in the context of waste picking in 2012.

-

Handling waste poses many health risks. Waste pickers are exposed to contaminants and hazardous materials, from fecal matter and medical waste to toxic fumes and chemicals. Those who work at open dumps face risks caused by trucks, fires and surface slides. Some must take collected waste home to sort or store, introducing dangers to the home. A lack of worker protection and poor access to health care aggravate these risks. Open dumps pose environmental and health concerns, but any dump closure must include a comprehensive and articulated approach that addresses the impacts on waste pickers.

Waste pickers endure ergonomic hazards such as heavy lifting and repetitive motion, and may experience back and other pain. In the Metropolitan Region of Belo Horizonte, Brazil, WIEGO’s Cuidar Project is working to build knowledge and capacity on key preventive measures that address these ergonomic problems.

God is My Alarm Clock: A Brazilian Waste Picker’s Story tells how waste picker Dona Maria Brás worked to set up cooperative ventures where waste picker members gain respect and security.

Waste pickers faced specific risks in the COVID-19 pandemic – from handling contaminated materials to losing essential daily earnings when governments ordered work stoppages and told people to stay home.

Policies & Programmes

Whether and how waste pickers are included in municipal waste systems varies greatly. Worldwide, most waste pickers are not recognized for their contributions and do not have access to state-sponsored social protection.

Where waste pickers are organized, this is changing. Membership-based organizations and allies are helping cities recognize the vital role waste pickers play and are encouraging authorities to design more progressive policies. Cities including Belo Horizonte, Lima and Pune are developing policies that integrate waste pickers into waste collection and recycling.

For other examples of regulatory initiatives with positive outcomes, see Waste Pickers and the Law.

-

An exclusionary policy environment harms livelihoods. In Bogotá and Durban, for example, regulations and by-laws regarding waste were a problem in 2012. Where states provide the legal framework for inclusivity, worker collectives can thrive, such as in Brazil where the National Solid Waste Policy recognizes waste pickers’ role.

-

A supportive policy environment positively impacts waste pickers’ livelihoods. For example, the Belo Horizonte municipality partners with waste pickers and their organizations, providing infrastructure, subsidies and worker education.

-

Multi-scalar climate governance is key to adaptation measures. At the global, national and local level, mechanisms and response measures aimed at steering urban systems towards adaptation to climate-change risks are needed. In cities such as Belo Horizonte, waste pickers and their allies are on adaptation committees and national climate-change forums.

-

After years of advocacy by Colombian waste pickers, the Constitutional Court of Colombia published a series of rulings that Bogota’s waste pickers must be included in municipal sanitation planning. These rulings establish the recognition of waste pickers, their role in the recycling value chain and their status as service providers in the waste management service. Although there have been challenges as well as achievements in implementation, as of 2019, there were 94 municipalities in Colombia with at least one waste picker organization providing the public service of recycling.

-

In 2020, the South African government published a Waste Picker Integration Guideline that was negotiated by stakeholders, including representatives of waste picker organizations.

-

In 2011, the government of Minas Gerais state in Brazil passed a law that created a monetary incentive,called the recycling bonus (bolsa reciclagem), to be paid to cooperatives for the environmental service they provide by redirecting recyclables into the production cycle. This payment is in addition to the payments catadores receive from buyers, and from municipalities for service provision.

Organization & Voice

Waste pickers are motivated to organize and fight for recognition. In an increasing number of cities, waste pickers have formed collectives to advocate for their inclusion in municipal planning of solid waste management. At the global level, the International Alliance of Waste Pickers (IAWP) – a global network of waste picker organizations representing 460,000 organized waste pickers across 34 countries – held its first Elective Congress in 2024, marking a major milestone for the movement.

Through the IAWP (formerly the Global Alliance of Waste Pickers or GlobalRec), waste pickers have taken the stage at international climate-change conferences and events to highlight the need for global policies that help, not hinder, their work.

In 2013, waste pickers’ organizations played an active role at the International Labour Conference, where “Sustainable Development, Green Jobs and Decent Work” was the theme.

A global database called Waste Pickers Around the World has been established with the support of WIEGO and the International Alliance of Waste Pickers.

For more, see Waste Pickers Organizing.

More Occupational Groups

-

Garment Workers

Learn More -

Domestic Workers

Learn More -

Street Vendors

Learn More -

Home-Based Workers

Learn More