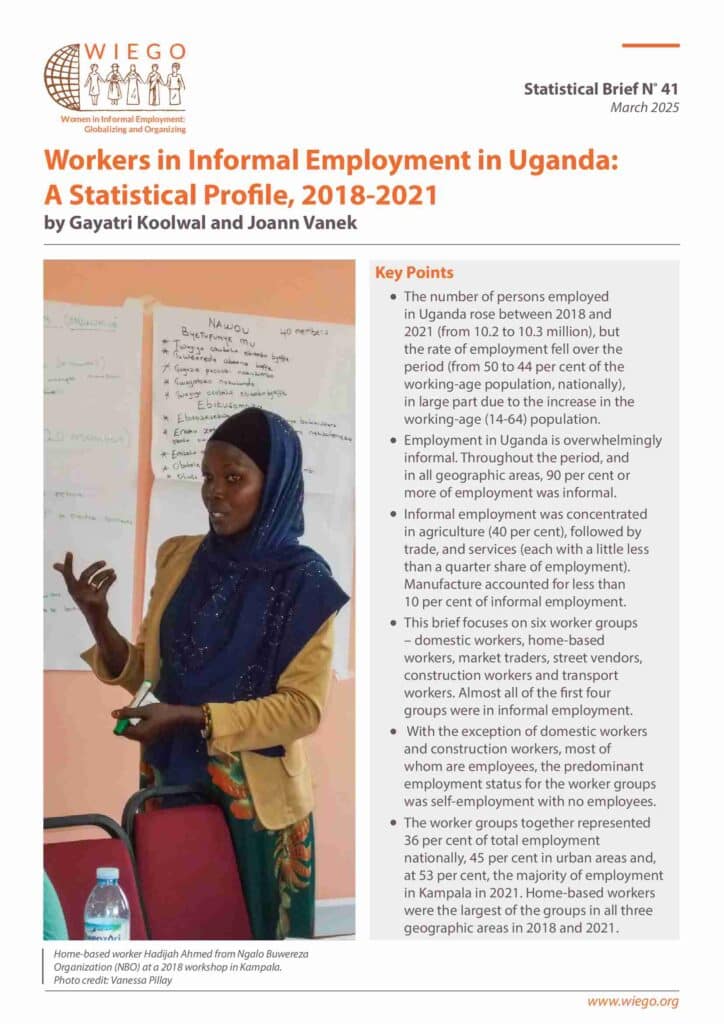

Viboonsri Wongsangiym and her husband, Bang Aree, produce Muslim garments in their home in suburban Bangkok. Like most home-based workers, the couple must deal with constraints typical to informal workers, especially irregular orders and inconsistent income. They joined HomeNet Thailand to access more benefits for informal workers and to connect to new work opportunities. Photo Credit: Paula Bronstein/Getty Images Reportage

Who Are Home-Based Workers?Home-based workers produce goods or services in or near their homes for local, domestic or global markets. They work in a wide range of industries: from assembling micro-electronics and providing IT services to producing and finishing textiles and garments.

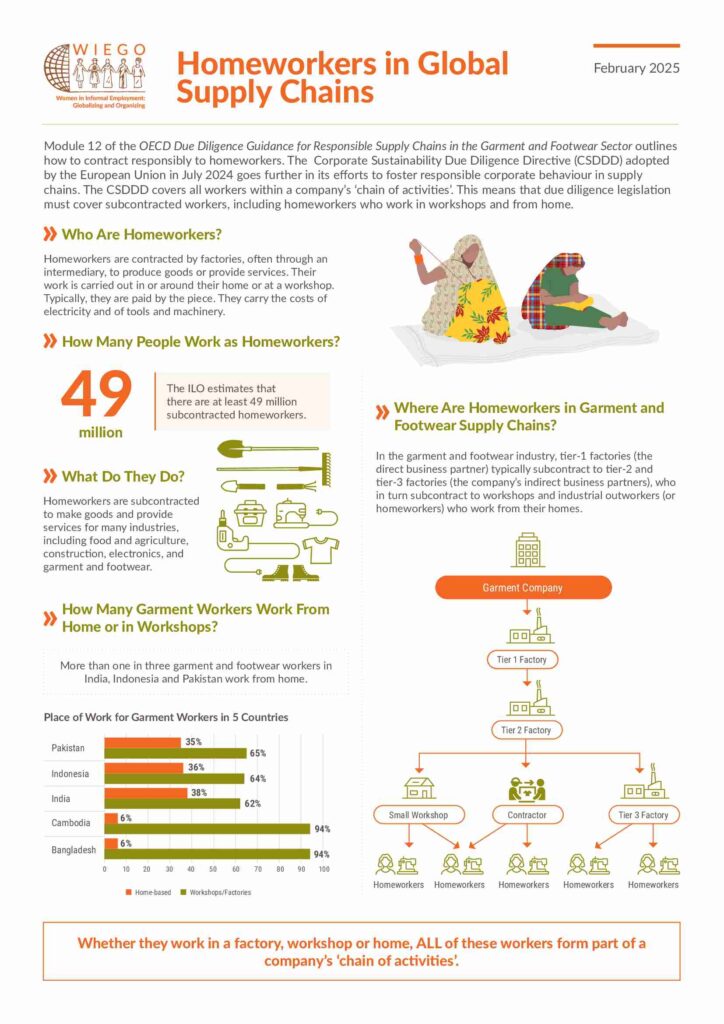

Globally, there are 260 million home-based workers. Home-based work represents a significant share of total employment in some countries, especially in Asia. Close to 148 million women do home-based work across the world, making it an important source of employment for women.

Across all industries, home-based work is a growing global phenomenon. Yet, while this massive workforce is vital to many supply chains, these workers are often invisible.

Featured Video: Who Are Home-Based Workers?

Defining Home-Based Workers

There are two types of home-based workers:

- Self-employed home-based workers buy their own raw materials, supplies and equipment and pay utility and transport costs. They usually sell their goods and services locally, but sometimes sell to international markets. Most do not hire others but may have unpaid contributing family members working with them. They assume all the risks of being independent operators.

- Sub-contracted home-based workers (called homeworkers or industrial outworkers) are contracted by individual entrepreneurs, factories or firms, often through an intermediary. Homeworkers may not know what firm they are doing work for or where the goods will be sold. Typically, they are paid by the piece and do not sell the finished products themselves. While homeworkers might be given the raw materials to work with, they have to cover many costs of production: workplace, equipment, electricity and supplies.

Note: While home-based work can be found around the world, in developed regions, home-based workers tend to be self-employed professionals or teleworkers, while in developing and emerging regions, home-based workers are more likely to be self-employed, industrial outworkers or contributing family workers engaged in more labour-intensive occupations.

Challenges & AdvancesStatistics on Home-Based Workers

WIEGO has produced Statistical Briefs that provide data on the numbers, working arrangements and characteristics of home-based workers. A statistical brief based on ILO data for over 100 countries provides global, regional and sub-regional statistics on home-based workers. A set of statistical briefs for four countries in Southern Asia presents detailed data on home-based workers at national, urban and rural levels. In addition, a set of statistical briefs on all informal workers in several countries includes data on home-based workers at the national, urban and city levels.

Counting this invisible workforce

There have been significant advances in improving statistical methods and guidelines to count home-based workers. WIEGO’s Statistics Programme has developed guidelines for estimating home-based workers and other groups of workers in informal employment. To develop a full statistical picture of home-based workers, information must be gathered on place of work, status in employment, type of contracts, and mode of payment.

In 2018, the 20th International Conference of Labour Statisticians took important steps to improve data on home-based workers, especially homeworkers, when it adopted a new International Classification of Status in Employment (ICSE-18). The ICSE-18 introduced a new category in the classification: dependent contractor.

Despite these advances, challenges to collecting reliable data remain. Some countries do not include questions on “place of work” in labour force surveys and population censuses; this question is key to determining who is a home-based worker. And often, enumerators are not trained to count home-based workers so they list these workers as doing only (unpaid) household work. Also, home-based workers may not perceive and report themselves as “workers”. This is particularly true of women home-based workers.

-

260 million

women and men produce goods or provide services from in or around their homes.

-

57%

of home-based workers in the world are women.

-

65%

of the world’s home-based workers are in Asia & the Pacific.

Additional Statistics on Home-Based Workers

-

Globally, 224 million (86%) of home-based workers are in developing and emerging countries, and 35 million (14%) are in developed countries.

More women (57%) than men (43%) globally are home-based workers. The share of women and men in home-based work varies according to country income group: In developing and emerging countries, the share of women and men are similar to those worldwide: 58% of women in comparison to 42% of men. However in developed countries, there are slightly more men than women; the anomaly is due to Europe, where men represent 58% of home-based workers and women 42%.

Learn more -

- In Thailand, almost 10% of the workforce – some 3.7 million people – were engaged in home-based work in 2017. Most are women, and over 70% work informally.

- In Bangladesh, the 10.6 million home-based workers (2016/17 Labour Force Survey) represented 17% of total employment.

- In India, there are 74 million home-based workers (44 million women and 30 million men), which accounts for 14% of total employment, and 29% of women’s employment and 8% of men’s.

- In Pakistan, the number of home-based workers increased from 3.6 million in 2013/14 to 4.4 million in 2017/18, while the share of home-based workers in total employment remained at 7%. The number of women home-based workers increased, while the number of men declined.

Home-Based Workers' Contributions

WIEGO’s Informal Economy Monitoring Study (IEMS) provides critical insights on the contributions made by home-based workers to their households, society and the economy.

Home-based workers are economic agents who create demand by buying supplies, raw materials and equipment. Self-employed home-based workers provide goods and services at a low cost to the public. They pay taxes on the raw materials, supplies and equipment they purchase and pay for transport and basic infrastructure services. Their earnings keep their households out of extreme poverty. And, while working from home, they can care for children and older people, making them important to the social cohesion of their communities and families. They also may have a lower carbon footprint than other workers since they often do not commute daily and rely on bicycles, walking or public transport.

Home-based workers also have links to formal firms since they buy supplies from, sell goods to or produce for formal firms in the supply chain. These firms then sell their finished goods, often charging sales taxes, which adds to the public coffers.

Driving Forces and Working Conditions

Home-based workers are found in all sectors of the economy and across geographic regions and country income groups, but their status in employment, occupation and the challenges they face vary by country income group.

In developing and emerging countries, home-based workers are more likely to be self-employed, industrial outworkers or contributing family workers. 83% of all home-based workers in developing and emerging regions (where home-based work is most prominent) are engaged in “sales and services” or “craft and trade”. These are labour-intensive occupations, such as food processing and producing garments and footwear, and include electrical and electronics work and building trades.

In developed countries, home-based workers are more likely to be employees, self-employed professionals and digital platform workers. In these regions, managerial, clerical and higher-skilled work, such as information technology, telecommunication, telemarketing and technical consulting, may be home-based. Digital platform workers who perform “crowdwork” from their homes are dispersed across all country income groups.

Though home-based workers share a common workplace, the challenges they face in developed versus developing and emerging countries are different. The challenges outlined below are predominantly faced by those in developing and emerging countries.

-

Although recent statistics show that 260 million people do home-based work for a living, policymakers tend to overlook home-based workers when they design policies, regulations or services. Labour force surveys and censuses do not always include questions on “place of work”, which would make this form of work more visible and allow for greater understanding of the sector through better data. The result is that most sub-contracted home-based workers are not covered under labour or employment law, most self-employed home-based workers are not covered by commercial law regulating contracts and transactions, and the homes-cum-workplaces of home-based workers often lack basic infrastructure services. Further, policymakers do not understand how wider economic trends impact home-based workers. Home-based workers tend to remain isolated from other workers in their sector, which limits their ability as individual workers to bargain in the market for more favourable prices and piece rates or to negotiate with the government for basic infrastructure and transport services.

-

Several factors, including financial need, drive home-based workers to do this work. Home-based workers’ earnings play a critical role in meeting basic household needs.

However, home-based workers earn very little, on average – particularly sub-contracted homeworkers, who are paid by the piece and depend on contractors or middlemen for work orders and payments.

The WIEGO statistical brief on home-based work globally found that those in developing and emerging countries generally worked longer hours than those in developed countries. In fact, while only 15% of women and 28% of men in developed countries worked 49 or more hours per week, in developing countries, 31% of women and 44% of men worked such long hours. In emerging countries, the percentages were even higher at 32% of women and 54% of men. (It is important to note that the data looked at only remunerative work; in most instances, women also have the child care and domestic responsibilities.)

-

More women than men are home-based workers globally: 57% of all home-based workers are women.Women turn to home-based work for reasons including a lack of formal training for formal-sector work, absence of child-care support, and social and cultural constraints on mobility. It is often argued that in megacities, the demands on women’s time – for care work and allied activities like collecting food rations or accessing basic services like water – reduce their participation in the economic sphere. In these contexts, home-based work provides a vital source of income for women and their families.

-

For home-based workers, their home doubles as their workplace – and therefore their home is an essential productive asset. This means that inadequate housing and poor infrastructure is a major challenge that impacts their health, earnings and productivity.

A small house hampers productivity, as the home-based worker cannot take bulk work orders because she cannot store raw materials and she cannot work continuously as there are competing needs for the same space by other household members and activities. Further, occupational health and safety is a critical issue for home-based workers, including ergonomic risks relating to poor posture from sitting on the floor or at low tables.

Urban service-related hazards that take a toll on the health and productivity of home-based workers include problems of sewage, open drains or non-existent drains, and poor waste management. Additionally, the time workers spend collecting water or disposing of garbage is time spent away from their market activities.

-

Home-based workers’ lives and work are deeply impacted by city policies, plans and practices, yet these are often not designed to support and protect homes as sites of work or the home-based workers themselves. Many municipal governments fail to recognize that many economically productive activities are situated in private houses and that most slum or squatter settlements and many informal houses are sites of production and distribution. Traditional urban planning and policy are reliant on a binary understanding of home and workplace. This traditional planner’s vision of strict separation between residential spaces and work spaces is fundamentally challenged by the home as a place of work. It is imperative that city planning integrates all informal workspaces to support the economy of work in domestic spaces.

-

COVID-19 restrictions led to a dramatic increase in working from home. Workers who used to commute to an office, both professional and clerical workers, began working from home using information and communications technologies (ICTs). But the traditional self-employed and (more so) industrial outworkers, as well as the contributing family workers who depend on them for work, saw a dramatic loss of work during COVID-19 and were left with no income for months.

A WIEGO-led study on the impact of COVID-19 found that most home-based workers were the least able to work during the peak lockdowns and restrictions in April 2020 and the slowest to recover by mid-2020, compared to domestic workers, street vendors/market traders and waste pickers in the sample. COVID-19 was not the first crisis to hit home-based workers hard. The global economic crisis that began in 2008 made it harder for home-based workers to make a living due to disruptions in global value chains and increased competition. The current cost-of-living crisis has exacerbated issues brought forth during COVID-19, including reduced demand for home-based workers’ services, a rise in the cost of raw materials and inconsistent work orders.

-

Many multinational firms based in the Global North outsource production to factories and homeworkers scattered across countries. Links between the homeworker and the lead firm are usually mediated by suppliers and their contractors and, thus, remain obscure. This can make it difficult to negotiate rates or receive payment for completed work.

Policies & Programmes

Structural changes are needed to address home-based workers’ lack of recognition as workers and exclusion from policy and planning. An important starting point is for national governments to recognize and promote home-based work as work and ensure their rights are protected under relevant labour laws and regulations. Local governments can also play a role by redefining their notion of what a workplace is and ensuring that home-based workers have access to basic infrastructure, improved housing and that their organizations participate in urban planning processes. Key to this structural change is protecting home-based workers’ right to organize and ensuring that they have a seat at the table whenever policies and programmes that influence their lives are created.

-

A Convention on Home Work (C177) was adopted by the International Labour Conference in 1996. C177 calls for national policies to promote equality of treatment between homeworkers and other wage earners. It also specifies areas where such equality of treatment should be promoted, including inclusion in labour force statistics.

Around the globe, home-based worker organizations are advocating to have their national governments ratify and implement C177. But more than 20 years later, only 10 countries have ratified it. However, some countries have adopted national legislation to protect home-based workers. The regional and global networks of home-based worker organizations and their affiliates continue their struggle for decent work.

-

Adopted in 2017, the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains in the Garment and Footwear Sector is a landmark framework that describes how companies can identify and prevent harms related to human rights, labour, environmental and integrity risks in their own operations and in their supply chains. Negotiated by business, trade unions and civil society, the document contains guidance to address several risk areas in the garment and footwear sector and includes a standalone module on homeworkers. This module directed at brands, buyers and manufacturers explains how to mitigate the violation of homeworkers’ rights and includes provisions that recognize homeworkers as an “intrinsic” part of the garment and footwear supply chain, their rights to receive equal treatment to factory workers and their right to organize as workers.

-

Several countries have adopted national laws and policies which recognize and protect homeworkers. HomeNet Thailand, with support from WIEGO and other partners, campaigned for more than a decade to win legislative protection for homeworkers based on Convention 177. Both the Homeworkers Protection Act B.E.2553 and a social protection policy came into force in Thailand in 2011. The law mandates fair wages – including equal pay for men and women doing the same job – be paid to workers who complete work at home for an industrial enterprise.

In Pakistan, home-based workers organized for nearly two decades for legislation. The Sindh Home-Based Workers Act, 2018 is the first piece of legislation in South Asia solely for home-based workers and enshrines the right to unionize and bargain collectively, social protection and access to dispute resolution mechanisms.

Following a decades-long campaign to improve the working lives of outworkers in the Textile, Clothing and Footwear industry by unions, allies and outworkers, Australia’s government passed the Fair Work Amendment (Textile, Clothing and Footwear Industry) Act, 2012.

-

The Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) has improved circumstances for home-based workers by representing workers on tripartite boards with government and employer representatives. Over the past four decades, policy advocacy has led to various sectors of home-based workers, including stitchers, bidi (cigarette) rollers and agarbatti (incense stick) workers, being included in the state schedules of the Minimum Wages Act. This has increased incomes. Also, Acts such as the Bidi and Cigar Welfare Fund Act, implemented in the 1980s, provide social security schemes such as health care, child care and housing for home-based workers.

-

Home-based workers need improved housing, adequate infrastructure and visibility in policy. At the local level, WIEGO has mapped home-based work in Delhi and what this means for planning and policy in the city. The aim was to find, support and document livelihood-enhancing urban regulations, housing and settlement design, and city planning with a view to supporting organizations of home-based workers in advocacy and interventions, as well as architects, urban designers and planners committed to inclusive practices. Alongside the Social Design Collaborative, the mapping provides insight into settlement typologies, density of built form, and where home-based workers’ nearest suppliers and buyers are located.

Much can also be learned from workers’ organizations: The Mahila Housing Trust works to improve the quality of habitats in informal settlements in Indian cities through its multi-pronged strategy to improve the physical environment, incorporate the needs of home-based workers in city plans and policies, and promote energy efficiency and climate resilience.

Organization & Voice

HomeNet International – a global network of membership-based organizations representing home-based workers – was launched in 2021, marking an important milestone in gaining global voice and visibility for home-based workers. It represents more than 1.2 million home-based workers from 75 organizations spread across 33 countries.

Organizing home-based workers can be challenging because they work in isolation. Even so, a growing number of organizations and national/regional networks have been formed – HomeNet South Asia, HomeNet South-east Asia and more. When home-based workers organize and have a collective voice, their ability to bargain increases. Some home-based workers also collectivize their economic activities by forming cooperatives.

Key demands of organized home-based workers include access to social protection and child care; secure housing tenure and affordable water and electricity services to support productive activities; inclusive urban planning and mixed use zoning regulations; and a safe and conducive working environment. For sub-contracted homeworkers in supply chains, additional demands are regular work orders and fair piece rates and, most fundamentally, that the ultimate brand should take responsibility for working conditions throughout the chain. And the self-employed need support in accessing markets and fair prices.

More Occupational Groups

-

Garment Workers

Learn More -

Domestic Workers

Learn More -

Street Vendors

Learn More -

Waste Pickers

Learn More