With Avi Singh Majithia

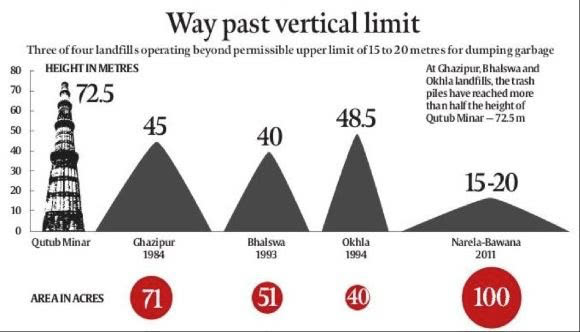

Delhi’s Qutub Minar, the tallest minaret in the world, rises high above many of the capital city’s landmarks, but will soon have less boastful competition: a growing mountain of waste that is now towering over the city.

The Ghazipur landfill has reached a height of 65 metres, just a few metres short of the Qutub Minar. The New York Times even took note in a recent article, “Mountains of Garbage Engulf India’s Capital.” What is not being acknowledged, however, is the role informal waste pickers play in managing the city’s waste and how current systems can better integrate their sophisticated knowledge in this area to manage a growing issue.

Meet the women and men sorting through modern India’s trash

Urban India is transforming, and so, too, are its waste problems. Increasing population and changing consumption patterns have accelerated solid waste production in Delhi. Today, the city produces nearly 10,000 metric tonnes of garbage every day. About 90 per cent of unsorted waste ends up in the dumps.

Source: Naveed Iqbal, The Indian Express, May 2016.

Source: Naveed Iqbal, The Indian Express, May 2016.

An army of “green” workers is almost invisibly keeping the city from being completely engulfed by its own discards. Estimates show that there are between 200,000-300,000 waste pickers in Delhi alone. The current civic waste management system would break down without the valuable contribution of these waste pickers.

The current civic waste management system would break down without the valuable contribution of these waste pickers.

A single waste picker collects, sorts, and transports anywhere between 10-15 kilograms of waste a day in Delhi. Waste pickers with tricycle carts can collect 50 kilograms a day. Their job is to collect and segregate household, commercial, and industrial waste for processing in centers, where it is sorted for composting, recycling or energy generation.

Stigmas and social prejudices

Despite waste pickers’ contributions, their work is not acknowledged, promoted, or protected. Instead, their social interaction is marked by prejudice and discrimination, and the waste pickers remain on the periphery — not just by virtue of their class, but also because of their low caste. A significant number of waste pickers in Delhi belong to socially marginalized populations, including scheduled castes, tribes, and other so-called “backward classes.”

In Delhi, there is historical evidence that scheduled castes (known as “Balmikis”), or low-caste workers who were traditionally associated with waste and sanitation work, were brought to the city from the rural villages to work on waste.

The Indian caste system, with its notions of “purity,” plays out with the waste pickers in a grotesque paradox of modern urban India. The cleaners of the city — those who collect others’ waste and recycle it — are perceived as contaminators and creators of waste.

A single waste picker collects, sorts, and transports anywhere between 10-15 kilograms of waste a day in Delhi.

The middle class often perceives the waste picker as being “dirty” and unhygienic. These caste issues mean Delhi’s waste pickers have to face burdens beyond those they share with their colleagues across the globe, including meager earnings, harassment, high health risks, and barely any access to social security.

New policy protects waste pickers but lacks implementation

The other paradox is that all this happens in a positive policy environment. The Solid Waste Management & Handling Rules (2016) has been a major policy win for waste pickers: for the first time, they have been officially acknowledged for their work to keep India’s cities clean. The policy also makes prescriptions for the inclusion of waste pickers and informal waste workers in waste management services.

The rules mandate that state governments institute measures and policies for registration of waste pickers and issuance of occupational identity cards, with the support of local bodies in urban and rural areas.

The Solid Waste Management & Handling Rules (2016) has been a major policy win for waste pickers

Representatives of waste pickers are to be included in respective state advisory committees on solid waste management, and the inputs of waste picker organizations are to be taken for framing the policies, strategies (and by-laws) on solid waste management.

These are all positive and welcomed steps — but not just on paper.

In fact, Delhi’s waste pickers are facing increasing marginalization. Unfortunately, the by-laws (framed after a delay of two years) have primarily focused on penalties. They have not detailed out how the rules can be implemented, including strategies for integrating waste pickers. The extent to which waste pickers have been covered under these rules is limited to definition and recognition as opposed to action on the ground.

Waste pickers demand action

Waste pickers are no longer willing to wait. A coalition of waste picker organizations from across Delhi are demanding that a clear path be laid out for recognition and integration, either by amending the existing by-laws or in any future waste management policies and strategies.

Their demands include representation in waste management-related policymaking processes as prescribed in the 2016 rules, including being given seats in state and municipal advisory and monitoring committees. They also demanded registeration and enumeration of waste pickers by the city.

Waste pickers play a critical role in taming the wild and growing beast that is solid waste in Delhi. Their role is the city’s waste management system needs to be recognized and promoted.

Last but not least, these organizations demanded that waste pickers in their organizations should be involved in waste collection and operation of waste management facilities.

Waste pickers play a critical role in taming the wild and growing beast that is solid waste in Delhi. Their role is the city’s waste management system needs to be recognized and promoted.

Besides implementing the 2016 solid waste management rules, local poverty-alleviation initiatives need to target the large number of urban poor who make their living from processing waste.

While India’s current government-led cleanliness push is welcomed, it must also create decent working conditions for waste pickers. Informal waste pickers are integral to the waste management system in the city. Their right to work can now only be ignored at the peril of the city being buried under its own waste.

Feature photo: Paula Bronstein/Getty Images Reportage

(1).jpg)