A wise person once said, “if the only tool you have is a hammer, then you tend to see every problem as a nail”. The reverse is true too: If you only see nails, you tend to think that the hammer will do the job. This analogy describes labour law. Labour law only “sees” employees. It resists the idea that self-employed workers in the informal economy, such as street vendors and waste pickers, should also be the subjects of labour law. Canadian labour law scholar Brian Langille describes it like this: the fundamental problem with labour law is that the “standard account of itself … makes it impossible to see the informal sector (no contract, no employer or employee) as part of labour law’s world at all.” Indeed, labour law excludes 45% of the world’s workforce.

Labour law was forged at a time when Keynesian economics dominated. The state was responsible for economic growth and it was imagined that everyone who wanted a job would find permanent, full-time employment. Labour law thus divides the workforce into two categories: employees, who are entitled to a suite of labour rights, including collective bargaining, occupational health and safety (OHS), and social protection; and independent contractors, who work for themselves and don’t need the protection of labour law. In fact, competition laws in most countries prohibit independent contractors – people working for themselves – from bargaining collectively because this is seen as small businesses colluding with one another. Of course the world of work has become much more complex since the advent of labour law, and labour law scholars have risen to the challenge of reinventing the discipline. But the prevailing view is that self-employed workers in the informal economy should rely on human rights law and regulations other than labour law to address their claims (for collective bargaining, OHS and social protection) to the state.

WIEGO’s panel – Collective Bargaining and Occupational Health and Safety for Informal Self-Employed Workers: Realizing ILO Recommendation 204 – at the Labour Law Research Network’s 6th conference held recently in Warsaw, Poland, aimed to challenge this. Marlese von Broembsen, WIEGO’s Law Programme Director, argued that in many cities in the global South, the streets – the workplace for street vendors and waste pickers – are sites of class struggle. All over the world, the middle class, the political elite and the state have aspirations of "world class cities" that resemble Dubai. Indeed, funded by the World Bank, many countries are embarking on urban renewal programmes that have involved revoking the permits of street vendors and the violent evictions of thousands of vendors from their place of work, the streets. Class struggle is what labour law seeks to regulate!

Street vendors want to bargain with local authorities for rights to access public space to trade, and for services in exchange for the licensing, permit and other fees they pay to local authorities. Various examples show how labour law could include street vendors and other self-employed workers: Street vendors in Liberia and Zimbabwe have organized and concluded collective agreements with local authorities. Collective bargaining laws for artists, truck drivers, domestic workers and Uber drivers in Australia, Canada and the USA show how these laws could provide a legal framework for street vendors to bargain collectively.

Pamhidzai Bamu, Law Programme Coordinator for Africa, problematized labour law’s idea of the workplace. Labour law understands the workplace as a property owned or rented by an employer. For street vendors, waste pickers, informal transport drivers and street musicians (to name a few), their workplace is the public space – streets, pavements and markets – because that is where their customers are.

The International Labour Conference decided in 2022 that OHS is a fundamental right, which means that all member states of the ILO must translate the OHS Conventions into national law, irrespective of whether they have ratified the Conventions. OHS laws usually state that employers are responsible for, and must carry the costs of, making a workplace safe. Bamu analyzed the ILO Conventions on Occupational Health and Safety to show that they apply to all workers in all workplaces, including to informal self-employed workers. OHS laws should therefore also apply to street vendors and, since local governments are in control of public spaces, local authorities must make their workplaces safe. This includes providing shelters to protect workers from the weather elements, supplying clean water and toilets for street vendors and their customers, and providing adequate lighting to ensure the safety of traders who operate at night.

It’s fair to question the practicality of this argument but, during the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries were forced to recognize that street vendors are critical to the food security of the country. Indeed, 18 African governments declared informal traders who sold food as essential workers. Our research on the laws promulgated in response to the pandemic in Africa, Asia and Latin America showed that in many countries local authorities were legally responsible for making the workplaces of these traders safe. During the pandemic, informal traders were recognized as essential workers and COVID-19 laws placed obligations on local authorities to make their workplaces safe. This shows that it is not an insurmountable problem for local authorities to assume responsibility for realizing the OHS rights of street vendors.

Jane Barrett, WIEGO's Organization and Representation Programme Director, addressed the practical problem of local authorities refusing to engage in collective negotiations with self-employed workers in the informal economy. She discussed the case of the African Reclaimers Association (ARO), which was being stone-walled by the Johannesburg local government. Since workers in informal employment cannot strike, they have to identify other sources of collective power. Drawing on the power resources approach, Barrett showed that ARO innovated. They identified novel forms of associational power to "encircle" the local authority, thereby forcing them to come to the bargaining table: ARO forged relationships and/or concluded agreements with 22 schools, 10 apartment-block body corporates, four residents' associations, a multinational company, the UN agency UNIDO, and multiple small-interest groups of citizens. It is hoped that the combination of this carefully built social power, combined with the existence of a newly negotiated national framework for waste picker inclusion, will combine to put pressure on the local authority to include ARO in Johannesburg’s waste management system.

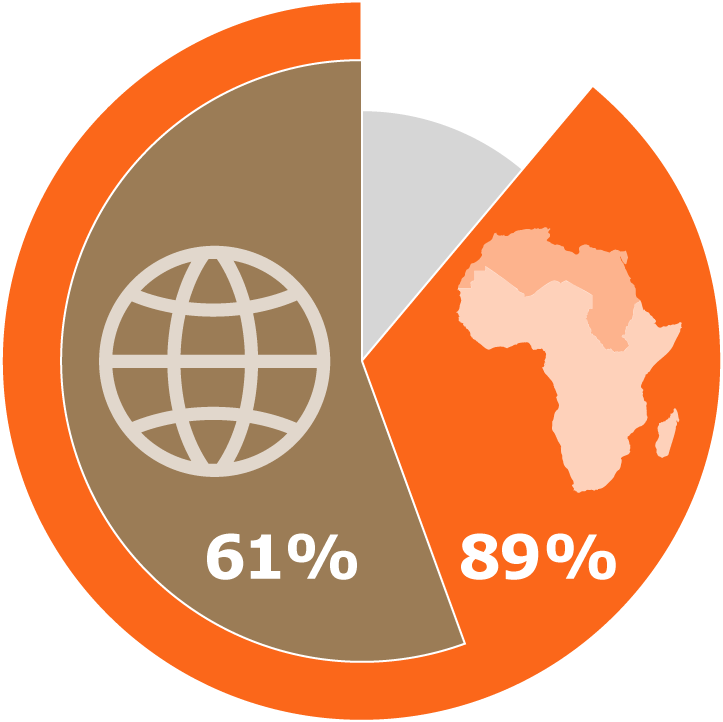

Judge Dennis Davis concluded the panel as our discussant. The Judge expressed the view that if 61% of the world’s workforce is in informal employment, of which 64% is self-employed, then this is the most pressing issue for labour law. In Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, 89% of the workforce is in informal employment, of which almost one in every two is a street vendor.

Judge Dennis Davis concluded the panel as our discussant. The Judge expressed the view that if 61% of the world’s workforce is in informal employment, of which 64% is self-employed, then this is the most pressing issue for labour law. In Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, 89% of the workforce is in informal employment, of which almost one in every two is a street vendor.

Indeed, if labour law does not cover most of the world’s workers, then to use the words of famous labour law scholar Harry Arthurs, it risks becoming "politically irrelevant and intellectually ossified".