A growing tax justice movement has been exposing the shadowy ways in which elites and large trans-national corporations often avoid paying their share of taxes — and the adverse effects this has on countries as a whole. For example, Oxfam has recently introduced a campaign to promote its Commitment to Reducing Inequality (CRI) Index, which measures how well an individual country’s national tax system redistributes resources.

Such efforts are clearly needed; however, they tend to mask some of the complexities in tax systems, particularly in the global South, where the vast majority of workers are in the informal economy. These complexities need to be better understood because the contributions of workers to taxes determine both how fair a country’s tax system is and how much tax is ultimately collected.

For the “missing middle,” taxes come in many forms

Informal workers often pay a bewildering array of national and local taxes, operating fees, rental fees, market tolls, and permit fees. While some countries have clearly defined presumptive tax systems, many of the “taxes”, tolls and fees that workers pay are not counted as tax contributions, according to the fairly narrow lens used by most tax experts. In reality, the experience of taxation in the informal economy ranges from a series of ostensibly well-meaning presumptive or “flat rate” measures to corrupt revenue collection practices backed by patronage networks.

In reality, the experience of taxation in the informal economy ranges from a series of ostensibly well-meaning presumptive or “flat rate” measures to corrupt revenue collection practices backed by patronage networks.

Despite their contributions, many workers fall outside of social protection schemes. They are the “missing middle” in many developing countries because they are not considered vulnerable enough to receive tax-funded social assistance, yet they also do not have access to contributory social insurance schemes.

What workers do and don’t get in return is important because it relates to how fair tax systems are perceived to be. Transparency and progressivity are key indicators of fairness. When citizens — and workers — understand what they get in return for paying both local and national taxes, they are more likely to pay them.

Willingness to pay relies on perceptions of “fairness”

One way to understand whether taxes, fees, and operating licenses are “fair” is to measure perceptions of, or attitudes towards, tax systems. Afrobarometer, a series of national public attitude surveys on democracy, governance, and society, recently undertook such an exercise by developing a module on taxation.

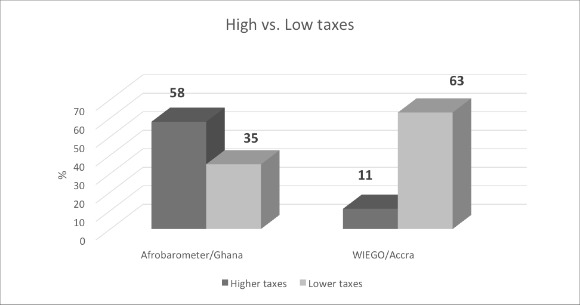

WIEGO researchers took advantage of this initiative by asking the same questions on taxes to a group of over 200 informal workers in Accra, Ghana. The comparison between responses to the Afrobarometer survey with those from three types of workers in Accra (market traders, street vendors and market porters — known locally as “kayayei”) offers some interesting insights into taxation in the informal economy.

When citizens — and workers — understand what they get in return for paying both local and national taxes, they are more likely to pay them.

Although most of the interviewees did not pay a tax on their earnings, about 30 per cent did. Also, over half paid a required daily tax to the Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA), and over three quarters paid some type of business license fee to the AMA. Just under a third paid a rental fee for their trading space.

When asked whether it would be better to pay high taxes in return for more public services or low taxes even if it means less services provided by government, most (63 per cent) of the informal workers we interviewed in Accra opted for lower taxes. In contrast, about 60 per cent of the respondents to the Afrobarometer survey indicated that they would prefer higher taxes if it meant better public resources.

Read "Take away these tolls: How Accra's poorest market workers got their wages back."

Informal workers’ views on taxes may differ drastically from those held by other Ghanaians because the benefits of paying taxes are less obvious. On the one hand, informal workers in Accra reported that it is relatively easy to find out which taxes and fees they are required to pay to local government (the AMA). Only about 43 per cent reported that it is difficult or very difficult to find out what taxes and rental fees they are supposed to pay to local government. In comparison, about 70 per cent of Ghanaians that participated in the Afrobarometer survey reported difficulty in finding out what taxes or fees they are supposed to pay.

What’s telling is a large difference in the perceived transparency in how the AMA uses the revenues from these fees and taxes. Most workers (66 per cent) reported that it is difficult or very difficult to find out how the AMA actually uses the revenues from workers’ taxes and fees. Compared to other citizens, it seems as though informal workers overwhelmingly find it difficult to see how their contributions to local government coffers are used.

Watch this video on tax policy and the informal economy.

Reasons for non-compliance also tell an important part of the story. In the Afrobarometer survey, the single largest reason for not paying taxes is that they are too high. Among the informal workers in our Accra sample, the modal response was poor service delivery (29 per cent). A relatively large percentage (25 per cent) also indicated that they could not afford to pay their taxes and fees.

Combining this finding with the one from the two previous graphs, it seems as though informal workers in Accra do not see clear benefits deriving from their tax contributions. This, in itself, is not altogether surprising (since attitudes towards taxation can be negative for a number of reasons), but the fact that attitudes towards taxation seem more negative among informal workers than among the population as a whole is telling.

Tax Justice “From Below”

Some of these findings might seem obvious. After all, aren’t negative attitudes towards paying taxes normal and why should we be concerned that informal workers might feel differently than other citizens? The short answer is that it is directly related to policy.

One of the more recent trends in a number of developing countries is to try to “draw informal workers into the tax net”. The argument is that the “social contract” between the citizenry and government was ruptured during the years of structural adjustment in many countries of the Global South and that, by raising taxes on informal workers, mutual accountability can be restored.

Compared to other citizens, it seems as though informal workers overwhelmingly find it difficult to see how their contributions to local government coffers are used.

One of the real risks of this approach, however, is that, if not done carefully and in partnership with workers in the informal economy, then existing vulnerabilities can be exacerbated. Many of the poorest informal workers (many of whom are women) have less leverage to negotiate with local government and this has the potential to make the taxation of informal workers regressive.

So while we should give our full support to ensuring that tax systems are progressive in developing countries and that large firms are prevented from both evading and avoiding taxes, we should also remain vigilant as to how informal workers are included in the tax net.

As the ILO’s Recommendation 204 on formalizing the informal economy is implemented, the issue of taxation as a pillar of the transition to formality may become a central concern in some countries. The results of this WIEGO survey of workers in Accra therefore provide a timely reminder that tax justice from below in the informal economy is likely to have a large impact on whether the process of formalization results in equity and fairness for the bulk of the workforce in the Global South.

Learn more about the informal economy.

Feature photo: ACCRA, GHANA: At Tema Station Market and Lorry Park, vendors situated on the pavement protect themselves from the sun's harsh rays with straw-hewn hats as they lay out their wares for sale. The vendors at Tema Station pay daily, monthly, and yearly licensing fees and tolls to the city government to enable them to operate there. Many street traders here are members of the Tema Station Traders Association, affiliated with StreetNet and the Ghana Trade Union Congress. Organizing provides a crucial platform for street vendors to seek empowerment and better conditions for their work. For example, the Tema Station Traders Association, with support from WIEGO, has participated in policy dialogues that enabled members to voice their needs and demands to the city government regarding congestion, evictions, sanitation, facilities, and security. Photo: Jonathan Torgovnik/Getty Images Reportage

(1).jpg)