As cities across the world shut down to stop the spread of COVID-19, governments are depending on a set of essential workers to continue to go out and work: to keep the public fed and informed, to care for the sick and vulnerable, and to maintain a clean and safe urban environment, among other critical services.

In the global South, many of these workers – such as street and market vendors, newspaper sellers, waste pickers and domestic workers – work in the informal economy. Their economic and working conditions were already precarious before the crisis. Now, without legal and social protections, they are working to sustain their families and ensure their communities have the food and basic services they need to survive – all at great personal risk.

From evicted to “essential” overnight

Although many informal workers are now considered to be “essential workers,” that was not always the case. Before the crisis, ongoing harassment by authorities, vilification in the media, and discrimination from the general public was commonplace. Their organizations were often not recognized as stakeholders in urban governance and not consulted on decision-making impacting their livelihoods.

In other words, they were treated as anything but essential – despite the critical contributions they have always madeto urban food, care, and sanitation systems.

However, the economic and public health emergency caused by COVID-19 has created a shift – there is a

Read The new crisis underscores old injustices in the informal economy.

Dire need for safety protection and income support

Although the recognition of informal workers as essential service providers is long overdue, they cannot be asked to continue their work without adequate protections and compensation. Accounts from essential informal workers in two of WIEGO’s Focal Cities shine light on the need for government and private sector action to ensure their physical and economic security as they continue to provide invaluable public services in a time of crisis.

Informing an anxious public: Lima’s canillitas keep the news coming

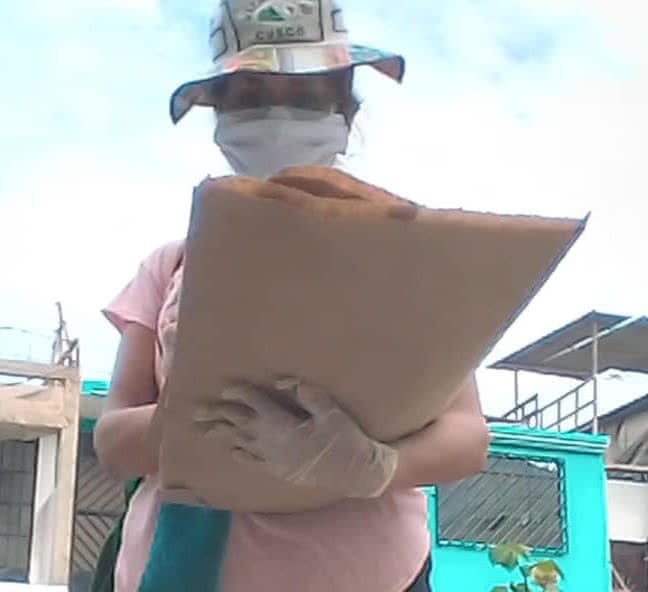

Juana Corman wakes at 2:00 a.m., as she has for decades, to travel across town to the distribution center where she picks up stacks of newspapers to sell. Normally, she would sell from her dedicated kiosk to passersby on Lima’s busy streets, but under Peru’s mandatory stay-at-home order, her work has changed. Now, she sells the daily paper house to house – delivering critical information to a city on edge.

During the crisis, Lima’s newspaper vendors, or canillitas, have received special permissions and praise from some of Peru’s best known journalists for the service they are providing. However, continuing their critical work during the crisis implies serious risks and costs. For example, public transport is difficult to access with drastically reduced metro schedules, and many canillitas are forced to hire taxis to travel long distances to work, cutting into their already reduced earnings.

Juana’s union has been advocating for the government to include them in the list of beneficiaries for the cash grants, or “bonos,” of 380 soles (or USD 110), which will be made available to vulnerable populations every two weeks during the crisis.

To provide canillitas with economic stability during the crisis, and to allow them to stay home if they are high risk, or if they become ill, Juana’s union has been advocating for the government to include them in the list of beneficiaries for the cash grants, or “bonos,” of 380 soles (or USD 110), which will be made available to vulnerable populations every two weeks during the crisis. As of April 5th, Juana’s union still did not know whether they would be included in the benefit.

The vast majority of canillitas are over fifty years old and urgently need access to protective gear – masks and gloves – to provide some measure of protection at work. While some of the publishing companies they distribute papers for have made efforts to provide these, others have not, denying any employment relationship or responsibility for the canillitas’ occupational health and safety. In response, some canillitas have been confiscating the advertisement section of the paper – a silent protest against papers who refuse to cede a fraction of ad revenue to protecting their foot soldiers.

While some of the publishing companies they distribute papers for have made efforts to provide these, others have not, denying any employment relationship or responsibility for the canillitas’ occupational health and safety.

In addition to the responsibility of the publishing companies to recognize the responsibility they owe to their distributors, and provide protections accordingly, Juana calls attention to the need for government action to provide health resources for the canillitas if they were to fall ill. “The government should consider canillitas, because of their high exposure at work, to be provided priority treatment in health centers – the same as doctors, nurses and police.”

Read about COVID-19's impact on street vendors.

Preventing food shortages: Wholesale market vendors and porters work around the clock to keep Lima’s food distribution networks running

At Lima’s largest wholesale market, Santa Anita, informal market porters and vendors provide a critical link in the city’s food distribution network. Every day, they receive and unload trucks full of produce from the countryside and sell it to groceries and vendors who fan out across the city to supply Lima’s massive metropolitan area with fresh fruits and vegetables. And every day comes with the uncertainty of whether they are exposing themselves to the virus in the process.

Since the start of the crisis, EMMSA, the public company that administers the market, has provided some protection by adding hand washing stations, but has denied responsibility for the provision of gloves and masks to market workers, insisting that the market workers’ organization, FENATM (Federación Nacional de Trabajadores de Mercados), use their own funds to purchase and supply this equipment to their members.

FENATM has made an effort to protect members as best they can – purchasing cloth masks from a fellow market worker who is producing them himself, for example. However, with limited resources, the purchase of disposable gloves and other necessary equipment is difficult. Since the crisis began, several members have fallen ill, while others have stopped coming to work for fear of getting sick. Others still are sleeping outside the market to avoid sleeping in crowded dormitories or going home and possibly passing the virus to their families.

The Federation continues to negotiate with EMMSA for protections and is attempting to appeal to the government labour inspection office to support the workers in their demands for a safe work environment, but so far, the only source of support for market workers is the Federation itself. As FENATM Secretary General explains, “We don’t have holidays, social security, pensions, none of that. Each worker does what he can with his job. The market workers are confronting this onslaught alone. This isn’t visible in the public sphere.” When asked if the workers in his sector felt protected, he said, “We don’t feel protected by the government, but rather by our own initiative.”

Listen to Sally Roever, WIEGO's International Coordinator, discuss what informal workers need in this crisis.

Keeping the metropolis clean: Waste pickers fill critical gaps in Mexico City’s sanitation infrastructure

Patricia Angeles has worked as a waste picker (or trabajadora voluntaria, as workers in her sector are called in Mexico City) for thirteen years. She is an expert at her trade – collecting household waste door to door and skillfully extracting recyclable material that she will later attempt to sell.

Patricia is part of an army of approximately 10,000 waste pickers in Mexico City who work within the solid waste management system – often side by side with formal sanitation workers – but receive no pay, social security or protections from the city for their labour. They earn a living only on the basis of voluntary tips from households and the occasional sale of recycled material.

Patricia is part of an army of approximately 10,000 waste pickers in Mexico City who work within the solid waste management system – often side by side with formal sanitation workers – but receive no pay, social security or protections from the city for their labour.

Even if waste pickers like Patricia had the luxury of savings to allow them to stay safely at home during the pandemic, their absence would put one of the biggest sanitation systems in the world under enormous strain at a critical time.

So Patricia continues to set out to work every day at 5:30 a.m., armed with her cart and her vast experience, but lacking critical protective equipment. The crisis only deepens the urgency of unmet needs that Patricia has dealt with for the past thirteen years, principal among them a contract with the city that would provide her with income and social security, paid sick leave, and other employment benefits.

Protective gear such as gloves and a mask have always been essential for protecting Patricia against hazardous materials. Now, they are even more so as she must deal with material that could be contaminated with the virus (the Mexico City government has failed to provide even formal sanitation workers with this gear during the crisis).

“The pharmacies don’t have masks, there is no hand sanitizer. I understand maybe people want to protect themselves, but the shortages are bad because the things we need to protect ourselves and our families aren’t there.”

Patricia has had to acquire protective gear herself and it has been difficult because of runs on supplies: “The pharmacies don’t have masks, there is no hand sanitizer. I understand maybe people want to protect themselves, but the shortages are bad because the things we need to protect ourselves and our families aren’t there.” She has made due with homemade masks and sanitizer her sister is producing, and she takes her own soap to work every day to wash her hands.

Because of the social distancing guidelines, fewer people are coming out to tip Patricia for her services, and her income has fallen at a time when her costs are rising.

The crisis has presented new challenges, as well. Because of the social distancing guidelines, fewer people are coming out to tip Patricia for her services, and her income has fallen at a time when her costs are rising. Her daughter’s school has closed and Patricia is trying to ensure she can access classes online, but doesn’t have the resources, “It’s difficult for me because we don’t have a computer, and we can’t use the phone for the classes, so we have to go to a cyber cafe and spend 30-40 pesos (USD1.20-1.60) on internet, which I don’t have right now, because there’s no people [to tip].”

Read about how the pandemic is impacting waste pickers.

Government and private sector must take action to protect frontline informal workers during the COVID-19 crisis

As these workers’ stories show, companies and governments continue to download costs and risks onto informal workers who are earning them profit and securing critical services for their constituencies in a time of crisis. Where informal workers are continuing to provide essential services, governments and private companies must treat their organizations as valued partners in the emergency response – consulting with them on the needs of their members and ensuring these needs are quickly and adequately met.

Informal workers have always been essential. They made invaluable contributions to their communities before the crisis, they continue to do so now at significant risk, and they will form a critical part of the recovery. However, their ability to do so safely and securely depends on the degree to which they and their organizations are supported with measures including those mentioned in these accounts: adequate protective equipment, income security such as emergency grants, social protections, and institutional recognition as

Read all the latest news and information related to informal workers and COVID-19 in our crisis information hub.

Feature Photo Credit: Juan Arredondo/Getty Images Reportage (Photo Credit Required) LIMA, PERU. J. Juana Corman Peréz sorts and collates inserts into newspapers on the street at dawn.

This article was developed in collaboration with the Focal Cities team.

Para leer este artículo en español, haga click aquí.

Pour lire cet article en français, cliquez ici.