Carmen Almeida, 56, worries about keeping in touch with her fellow domestic workers. Most haven’t worked since early March when Peru’s lockdown began, and the few who have kept working have been isolated in their employers’ homes, prevented from visiting their own families. She has managed to mobilize some donations, including one that is meant to help with communication. But “you can’t eat a telephone,” she said, indicating the extent of desperation many find themselves in several months after the crisis began.

Stories like Carmen’s are commonplace across the world in the wake of the initial COVID-19 lockdowns, with countless informally employed workers facing a brutal reality of reestablishing their livelihoods. Nearly a year into the COVID-19 pandemic, there is broad recognition that global progress toward reducing poverty has suffered a severe setback given its disproportionate impact on vulnerable populations. The United Nations estimates 71 million additional people living in extreme poverty, and the ILO estimates labour income losses of $3.5 trillion in the first three quarters of 2020, due to the pandemic.

With 4 billion people excluded from social protection, and GDP growth for the year projected to be negative, the historic magnitude of the crisis calls for an unprecedented investment in getting people back to work. Yet there is no blueprint for doing so in today’s global economy, where 61 per cent of employment is informal. What can be learned from the experience of informal workers during the course of the crisis?

Data from the first round of the WIEGO-led COVID-19 Crisis and the Informal Economy Study in 12 cities point to three common patterns across worker groups and continents. The first is a sudden and massive drop in earnings. Given that many informal workers earn day-to-day to meet basic needs, and given the links between informal work and poverty even before the pandemic, this disruption in earnings had severe consequences for workers and their households. Second, the reach of emergency cash transfers and food relief in the initial months of the crisis was limited and uneven. Third, as a consequence, workers have resorted to coping strategies that erode any assets they may have accumulated, leaving a long road to recovery ahead.

What Happened to Earnings Once the Pandemic Hit?

The initial wave of lockdowns severely disrupted markets and supply chains in March and April, and the shockwaves immediately hit workers’ earnings. Though national and city approaches to lockdown shaped workers’ experiences, in all 12 cities, the drop in income was severe.

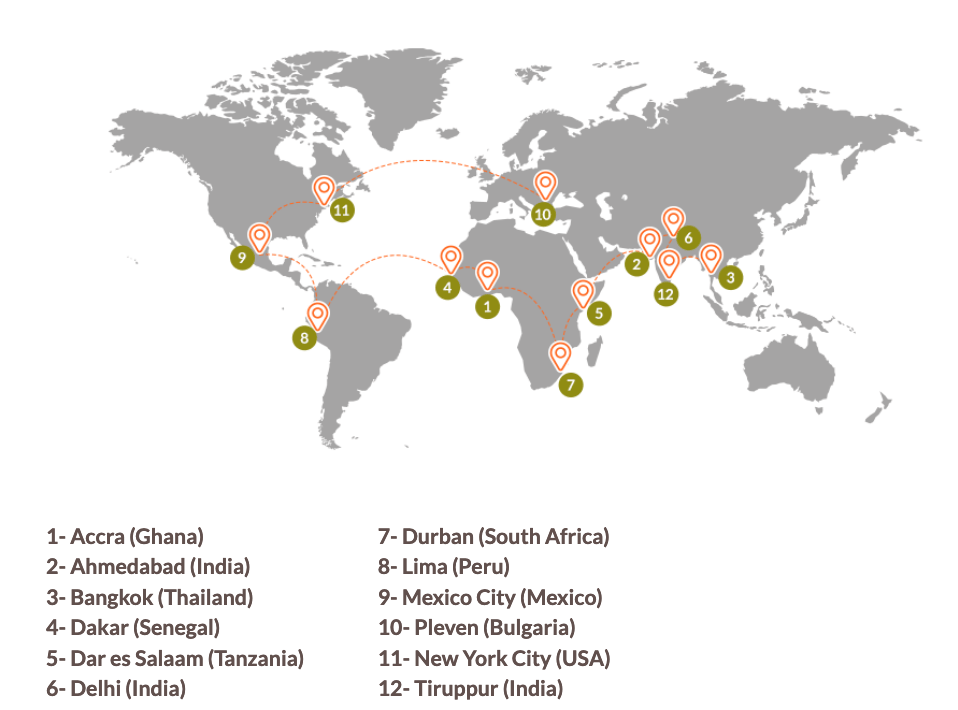

Cities in the WIEGO-led COVID-19 Crisis and the Informal Economy Study

In cities with strict lockdowns, work came to a near-complete standstill. In Ahmedabad, harsh lockdown measures were enacted very early—resulting in 97 per cent of domestic workers, 92 per cent of home-based workers, 96 per cent of street vendors, and 98 per cent of waste pickers reporting zero earnings during the height of the restrictions. Workers in Lima reported a similarly severe disruption.

In cities where restrictions were less severe, the extent of immediate disruption varied more across worker groups. Massage workers in Bangkok, for example, were put out of work entirely as physical distancing measures were put into place. Tourism industry workers in Thailand were also hit hard. But for some other sectors the experience was more mixed, with some street vendors, waste pickers and domestic workers reporting at least some earnings.1

Regardless of these variations, across the study worker groups experienced significant disruption to earnings. In every city except Dar es Salaam, study participants’ average earnings during the peak restrictions were less than half what they were in February, before the lockdowns began. And in half of the cities in the sample—Ahmedabad, Delhi, New York, Lima, Durban and Tiruppur—reported earnings in April were less than 20 per cent of reported earnings in February. In Ahmedabad and Durban, April earnings had decreased by about 95 per cent from February.

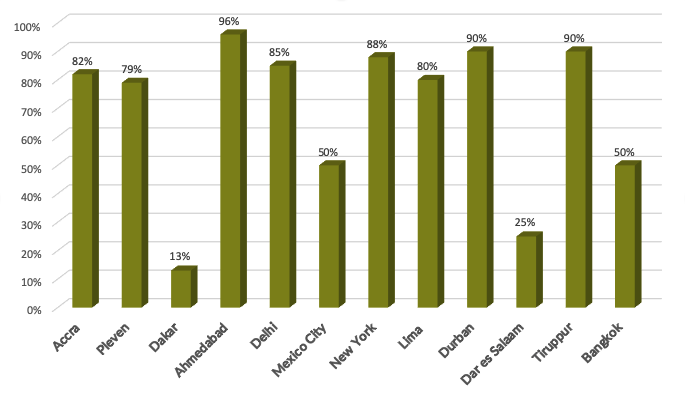

These severe drops in average earnings reflect both the high proportion of workers who earned nothing at all (Figure 1) and the weak demand for goods and services among those who could continue working. Across the full study sample, 69.8 per cent of all respondents reported zero earnings during the lockdown period. For those who continued working, demand for their goods dropped steeply.

Figure 1: Percentage of workers surveyed that reported ‘zero earnings’ in April 2020, by city

Even by June and July, when some lockdown measures had eased, most city samples reflected average earnings that were less than half of pre-COVID-19 earnings. For some workers, like street vendors in Accra, it was because police officers were blocking the transport of goods. A home-based worker in Pleven reported that customers were no longer buying non-essential goods such as souvenirs and jewellery. In Durban, police were blocking waste pickers from getting to their collection points and harassing anyone carrying recyclable materials:

We don’t have access to hotels and retail shops that we used to have before lockdown. They do not allow us to collect waste anymore [for recycling]; Durban Solid Waste collects it and throws it to the landfill...When we try and collect somewhere the police take away our recyclables.

Similarly, a street vendor in Lima reported the loss of both savings and workplace as a result of actions taken by local authorities to clear the streets:

The eviction and the confiscation—they took away my workplace, my capital, and my longtime savings from selling my products.

Several respondents spoke of the impact of lost earnings on physical and mental health, and of the need to shift consumption patterns, including food consumption. In four of the cities— Pleven, Lima, Durban and Tiruppur—well over half of the sample reported that household members had gone hungry in the month after the lockdown had ended. In four further cities—Accra, Dakar, Ahmedabad and Delhi—more than a third of workers reported that a member of their household had gone hungry.

Did Cash and Food Assistance Fill the Gap?

The sudden loss of employment prompted governments worldwide to consider relief measures, including emergency cash grants and food assistance. Some, but not all, of the countries included in the study implemented such measures.

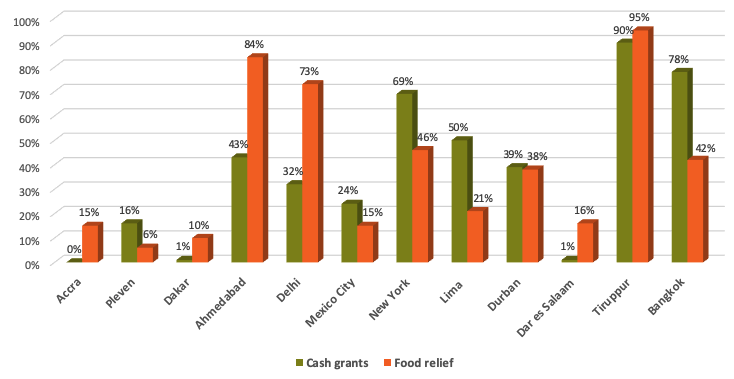

Where cash and food relief measures were implemented, the reach was limited and uneven. Across all 12 cities, about 40 per cent of workers reported getting food or cash from the government.2 Again, the approaches differed significantly, with cities like Dakar giving no cash support and minimal food assistance, and in Tiruppur 90 per cent of workers received cash grants (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Percentage of workers surveyed reporting receipt of cash grants or food relief, by city

Access to food relief was relatively high in the three Indian cities—Ahmedabad, Delhi and Tiruppur—because of the role that study participants’ organizations played in facilitating access. In Ahmedabad, for example, one key informant reported that SEWA (Self Employed Women’s Association) facilitated food rations, masks and hand sanitizer; provided information to members on where to go for health cards; and created an interest-free revolving credit scheme for vendors to buy stock. Similarly, HomeNet Thailand in Bangkok played a crucial role in supporting members to access cash grants by registering them on the relevant government website and troubleshooting other obstacles to access.

In other cities, workers in the study had more difficulty accessing cash grants and food relief. In some instances, governments lacked the necessary relationships or political will to distribute relief to informal workers. Said one key informant in Ghana, where just 15 per cent received food relief, “I think the government had its own means of identifying those to give the relief items. It was mainly the municipality leaders, NGOs, political party aspirants and other civil society organizations...but as to whether they involved the informal workers I don’t know. A lot of [workers] complained of not receiving the packages.”

How Did Workers Cope with the Losses?

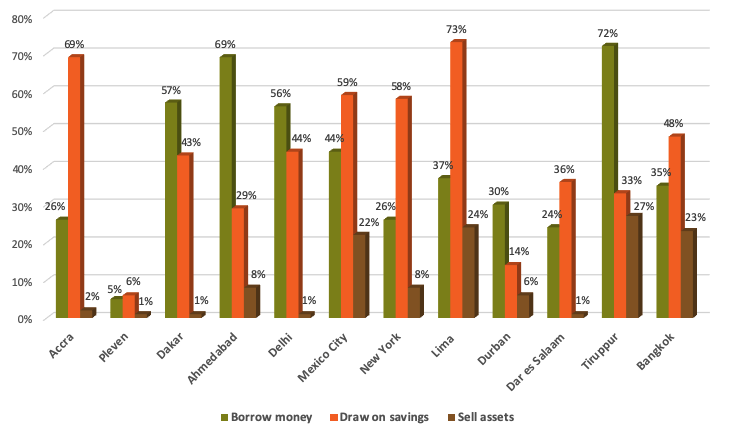

With the drop in earnings and lack of governmental support, workers resorted to coping strategies that will significantly reduce their ability to bounce back financially from the crisis. Many informal workers dipped into savings, borrowed money, and pawned off their assets—and because so many of these workers earn on a day-to-day basis, getting these assets back is a long-term challenge.

Drawing down savings

Workers reported digging into savings to make up the shortfall from their loss of earnings. This was such a widespread practice that only in two of the 12 cities did less than a quarter of respondents do so. Interviews also suggest that where respondents did not draw down savings, the reason may be that they earned so little before the pandemic that they lacked savings altogether.

All of this was a surprise. We feel scared and worried because we didn’t have any savings to survive that whole time [during the lockdown] and we couldn’t work. We stayed at home to protect our health, but now we are worried about what we’ll live on.

As for where the money was spent, many interviews showed savings were being used to pay basic bills, like rent and utilities, especially electricity.

Figure 3. Percentage of workers surveyed reporting each coping strategy, by city

Borrowing Money

Another common (43 per cent of the total sample) coping strategy was borrowing money or extending credit. In four of the cities, the vast majority of respondents reported taking on debt as a coping strategy. This was particularly prevalent among workers in Ahmedabad, where the lockdown restrictions were among the most severe. Their recovery will be hindered by having to pay off these new debts at the same time they try to reestablish livelihoods.

Interview data cite a range of lending sources. In some cases, workers relied on the employment relationship for lending sources: some domestic workers, for example, borrowed from their employers, and some home-based workers borrowed from intermediaries. In Dar es Salaam, among those domestic workers who lost their jobs in April, 71 per cent borrowed money from family, friends or neighbours.

Many workers relied on their personal networks to find lending sources. According to Mohamed Attia, Director of the New York Street Vendor Project at the Urban Justice Center, in April 2020,

It was a really terrifying moment and everyone was talking about not only how they were going to sustain the business for the very first few weeks, everyone was so worried about their personal life, their housing issue, their financial ability to just make ends meet to put food on the table. A lot of people were like, ‘we've been without income for a month. We had to borrow money from our family in Egypt. We had to borrow money from our friends.’ Especially folks who don't really have access to other financial resources, some people were in a slightly better position than others. They have credit cards, they have some savings. But others, who didn't have any safety net, no credit cards, nothing to rely on, it was all about the family and the friends and literally borrowing money from the people around you just to keep things going and to put food on the table and that was the bottom line.

Workers in several cities named rent, electricity, water and telephone bills as the reason they have had to take out a loan—and once a worker has taken a loan to pay a bill, she then has to find a way to repay it in circumstances where demand is down and earnings are only a fraction of what they used to be. According to one informant in Bangkok:

In a situation like this, [motorcycle taxi] drivers had to take more informal loans because government funds require certain conditions, details on documents, and a long time to process. Some people are blacklisted. However, informal loans will pile up. For instance, one takes a loan from Creditor A. If they are unable to pay up as agreed, they will go and get a loan from Creditor B to pay to Creditor A...When they cannot pay up, they would go to Creditor C, and the vicious cycle goes on and on.

Selling or Pawning Assets

Shedding assets was a less common strategy, only reported by 10 per cent of respondents, but leaves poor households financially hamstrung, as assets are often acquired over a long period of time. It is also an indicator of desperation in the face of lost earnings and the risk of hunger.

Roughly a quarter of workers in Mexico City, Lima, Tiruppur and Bangkok reported the sale or pawning of assets as a coping strategy. This was particularly the case among waste pickers in Mexico City and Lima where 42 per cent and 50 per cent, respectively, sold assets in order to survive.

Where workers are pawning economic assets in order to get by, their chances of recovery dwindle further. This is especially the case where informal money lenders take advantage of workers’ desperation by luring them into high-interest, predatory loans that require collateral.

The experience of a home-based worker in Bangkok speaks to this trend:

Money-lender agents visited the informal garment community and offered informal loans, such that informal garment workers pawned their sewing machines as collateral. Borrowers pay 100-200 Baht a day in interest. The loan sharks confiscated the sewing machine upon default of the payment.

Relief, Recovery and the Road Ahead

When asked about the months ahead, some study participants indicated an ongoing need for cash grants and food relief just to survive, especially for older workers who are expected to stay home due to the danger of contracting COVID-19. Others emphasized the need for long-term, systemic measures, above all finding ways to extend social protections to workers like them, who are commonly excluded by both poverty-based protections and employment-based protections. Study partners in several cities have worked with governments to help informal workers get access to short-term, temporary relief measures as well as long-term, systemic social protection measures. These efforts represent an essential piece of the recovery puzzle.

But perhaps the most common perspective from workers in the study was that they simply need to get back to work. Crucially, policy makers must understand that getting people back to work in a way that will lead to meaningful recovery requires a serious commitment to making working conditions better than they were before the pandemic. Vulnerability to the effects of the COVID-19 crisis is no accident. It is severe and widespread precisely because of the lack of protections in place for the majority of the world’s workers. The experiences of participants in this study make clear how a lack of protection creates multiple pathways through which a global crisis impacts workers.

Rhetoric around ‘building back better’ must be accompanied by ambitious policies that restore livelihoods with markedly better terms for workers. This will help economic recovery and build better governance practices—ones where those in public office can work alongside those in the informal economy to find solutions around providing goods and services safely. Organized workers are essential partners for governments, both national and local. They know what is needed to get back to work under better conditions. The question is whether governments will listen.

The WIEGO-led COVID-19 Crisis and the Informal Economy Study was carried out with generous support from the International Development Research Centre.

End notes:

1. 100 per cent of the massage worker sample reported zero earnings. But 28 per cent of home-based workers, 45 per cent of street vendors, 66 per cent of waste pickers, and 80 per cent of domestic workers in Bangkok reported at least some earnings in April.

2. 36 per cent reported receiving a cash grant while about 38 per cent reported food assistance from government.

Find more information on the COVID-19 and the Informal Economy study here.

Photo: Christina has been in business for 20 years and currently trades along the footpath to the Tema Lorry station in Accra, Ghana. She has four dependants, including her sister’s children who she has been caring for since her sister died. Credit: Benjamin Forson