Supermarkets have spread rapidly across the Global South, but what implications does this growth have on informal food retailers and the food security of low-income households?

For over 10 years, the African Centre for Cities (ACC), at the University of Cape Town, has worked on urban food security, conducting detailed research in 15 cities across Sub-Saharan Africa initially through the African Food Security Urban Network (AFSUN) and more recently through the Consuming Urban Poverty (CUP) project, as well as across the Global South through the Hungry Cities Partnership.

This research has consistently shown the importance of the informal economy in the urban food system, and particularly in the food security of poorer households.

WIEGO’s Urban Research Director, Caroline Skinner, has been an advisor to ACC’s food security research team. In this interview, she and food security expert, Gareth Haysom of the ACC, reflect on this decade-long evidence and what it means for feeding cities.

Given the rapid expansion of supermarkets, are consumers still patronizing informal sellers?

ACC’s survey evidence consistently finds that low-income households continue to source food from informal outlets, even when supermarkets are in the area.

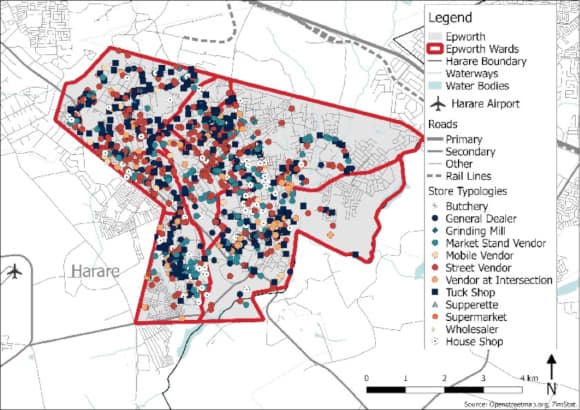

By way of example, the Consuming Urban Poverty (CUP) project conducted fieldwork in three secondary cities: Kisumu, Kenya; Kitwe, Zambia; and Epworth, outside Harare, Zimbabwe, and the vast majority of those interviewed patronized the informal food economy — from street food vendors to house shops to market sellers selling a variety of foods from vegetables to pulses to meats. In Epworth, this was as high as 79 per cent, with over 50 per cent doing so every day. In Kisumu and Kitwe, over 70 per cent of households purchased food from informal outlets more than 5 days a week.

Low-income households continue to source food from informal outlets, even when supermarkets are in the area.

These results echo the findings from AFSUN surveys: across the 11 cities, 70 per cent of households interviewed reported normally sourcing food from informal outlets. Nearly one third said they patronized the informal food economy almost every day and nearly two thirds did so at least once a week.

What we are finding is rather than simply displacing informal trade, supermarkets and informal traders coexist.

What does this research show about usage of supermarkets by low-income shoppers?

While low-income consumers are doing their daily shopping in the informal food economy, they are indeed still using supermarkets.

In CUP cities, most interviewees reported patronizing supermarkets, while the AFSUN research found that 79 per cent of interviewees purchased from supermarkets, but most respondents reported shopping at supermarkets just once a month.

In Kisumu and Kitwe, over 70 per cent of households purchased food from informal outlets more than 5 days a week.

The existing evidence suggests that there was a pattern of bulk-buying staples from supermarkets while relying on the informal food economy for other daily food needs.

What explains the continued use of informal retailers?

Informal food retailers remain adept at responding to the needs of poor urban residents. For these consumers, their income is erratic; they may lack refrigeration and storage space; and they use public transport or taxis, which limit the quantities that can be transported.

Challenges like these force low-income households to purchase food more frequently. The research suggests that the urban poor will continue to choose to source food in the informal sector due to a combination of factors:

- Convenient location: Informal food traders are often located at commuter points, while mapping of informal food outlets shows how evenly distributed they are through urban settlements. Consumers, therefore, do not have to incur additional transport costs to purchase food.

- Opening hours: Surveys with informal traders consistently show they often open early and close late.

- Appropriate quantities: Informal food retailers often break up bulk products to sell in smaller quantities, which might be more expensive per unit, but is more affordable to the urban poor.

- Credit: Informal food traders often offer credit, making it possible to buy food without cash in times of shortage.

Such strategies mean that the informal food sector plays a central role in enabling food access and, as a result, improved food security for the urban poor.

It is often assumed that supermarkets are a boon for poorer households. What does ACC’s work show about their impact on food security?

The research findings suggest supermarkets are most certainly not always a boon for poorer households. In a study conducted in Cape Town, Jane Battersby found that supermarkets in low-income areas often stock less healthy foods than those in wealthier areas.

This research has consistently shown the importance of the informal economy in the urban food system, and particularly in the food security of poorer households.

Therefore, it should not be assumed that supermarkets increase access to healthy foods. In the Cape Town research, they concluded that, since supermarkets stocked processed food, they had, in fact, accelerated the transition to less healthy diets.

The state does have a duty to protect consumer health. Food produced under informal conditions — without access to water, toilets and shelter — must surely be an issue?

We certainly must not discount consumer safety issues.

Levels of bacteria in street food have been measured in many urban areas across the African continent. The results show that the prevalence of bacteria in street foods vary from high to low. The decisive factor in this is the extent to which traders have access to basic infrastructure (water and toilets) and trading infrastructure (shelter, tables and paved surfaces).

For these consumers, their income is erratic; they may lack refrigeration and storage space; and they use public transport or taxis, which limit the quantities that can be transported.

These findings suggest that the more informal traders are incorporated into urban plans, the safer the food they sell. Hygiene training is also shown to be an important factor in securing low bacterial counts.

Urban agriculture is often a focus of current policy initiatives to improve food access and security. What do your findings suggest about this focus?

In all the cities researched, food was available. Formal and informal food traders use multiple local, national and international networks to secure enough food to sell.

The more informal traders are incorporated into urban plans, the safer the food they sell.

Food insecurity is rather the result of the ability to purchase food. The research conclusively shows urban agriculture is seldom a primary food source and those who do practice it very seldom sell the surplus they produce.

This suggests that a policy focus on urban agriculture might be misguided.

What policy suggestions would you make, given the findings in this research?

The research shows that informal food traders are key enablers of food access and contribute to the stability in the urban food system. In addition, informal food trade is a significant source of employment, particularly for women.

Rather than constantly being harassed, informal food retailers should be incorporated into urban plans. The CUP project has developed a number of policy briefs to assist and guide local government. WIEGO’s work on inclusive public space, drawing on good practices from a range of countries and cities, provides suggestions for a participatory approach to planning, design and management of trading spaces, guided by progressive legislation.

Both the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) recognize the importance of informal food retailers and have produced excellent guidelines for improving the health and hygiene standards of informal retailers.

Download WIEGO’s toolkit for Supporting Livelihoods in Public Space

Feature photo by Jane Battersby taken in Kitwe, Zambia.