As COVID-19 continues to spread in late 2023, new booster vaccines are awaiting approval. The health of billions of workers could be protected if they all had access to vaccination. Unfortunately, past experiences have taught us that despite their essential contributions to society and high exposure to the virus, workers are often excluded from vaccine drives. A closer look at seven countries shows how worker organizations have secured vaccine access for their members over the past two years.

South Africa

The African Reclaimers Organisation (ARO) is a membership-based organization of reclaimers and waste pickers based in and around Johannesburg, South Africa. At the beginning of the pandemic, they distributed food donations to their members who were experiencing financial hardship. While doing this, they educated them about the COVID-19 virus. As the pandemic progressed and new preventative tools became available in the form of COVID-19 vaccines, “it got to the point where we were teaching about vaccination”, explains Eva Mokoena, one of ARO’s leaders.

Across the organization, ARO leaders began sharing knowledge with members on the importance of getting vaccinated – adopting a “train the trainers” approach to passing on information. Many of ARO’s members are migrants from other African countries and some do not have immigration documents, such as ID cards or passports. ARO assists its members with obtaining affidavits that allow them to be vaccinated without the need to produce documents.

ARO’s work occurred within a difficult context of xenophobia – with migrant members harassed by police for their paperwork – and discrimination by health-care professionals associated with societal perceptions of the reclaimer occupation. As Eva recounts, “when they know you’re a reclaimer, they think of someone who’s dirty”.

Kenya

Members of the Kenya National Alliance of Street Vendors and Informal Traders (KENASVIT) – a Kenyan national alliance of street vendors, market hawkers and informal traders – also experienced harassment from the state, in particular in the early phase of the pandemic. But, as their representative Anthony Kwache shares, KENASVIT began engaging with the state to uphold members’ rights to vaccination: “when the vaccine came in, most of our affiliates were working very closely with the county government and national authorities to increase workers’ access to vaccination”. This involved bringing COVID-19 vaccination programmes directly to their members, with vaccinators coming to markets. KENASVIT members were thus spared long waiting times at health-care facilities. This approach was the result of KENASVIT’s engagement in a governmental committee that was tasked with supporting the Kenyan government to reach street vendors and traders in their work and social spaces.

Malaysia

In Malaysia, migrant domestic workers have been organizing themselves in the face of labour exploitation and denial of their right to health care, which has intensified since the onset of the pandemic. Domestic workers have reported being on call for 24 hours every day, increased workloads, increased stress and social isolation, discrimination in health facilities and facing unaffordable health insurance coverage.

According to the Association of Indonesian Migrant Domestic Workers (PERTIMIG), domestic workers experienced challenges in accessing the Malaysian vaccination scheme. PERTIMIG members in rural areas without phones were unable to use the government mobile application required to register for vaccination. Some members were forbidden by their employers to register for vaccination. Undocumented workers were concerned that registration data could be traced to their immigration status and put them at risk of arrest or deportation. In response, PERTIMIG educated its members on how to register for the vaccine, and on their rights as documented or undocumented workers. They also helped members to negotiate access to vaccination with their employers. “We empowered members to speak to their employers about the importance of vaccination”, said a PERTIMIG representative.

Asosasyon ng mga Makabayang Manggagawang Pilipino Overseas (AMMPO), an association for domestic workers from the Philippines in Malaysia, reported an increase in the number of immigration raids, creating more risks for domestic workers. “Migrant domestic workers don’t want to come out for vaccination because they are scared,” shared an AMMPO representative. Like PERTIMIG, AMMPO educated their members on their rights to vaccination, while being sensitive to vulnerabilities surrounding immigration status. They have provided information using online seminars and leaflets.

Indonesia

In neighbouring Indonesia, domestic workers’ organization Jaringan Nasional Advokasi Pekerja Rumah Tangga (JALA PRT) also advocated to increase access to vaccination for its members. They lobbied the Indonesian Ministry of Women Empowerment and Child Protection to provide vaccines for domestic workers, taught members how to use the mobile application for registering for vaccination, and printed out their proof of vaccination.

Kuwait

Sandigan is an organization for the rights of Filipino domestic workers based in Kuwait, where domestic workers make up a significant share of the population. They noticed that members’ inability to get vaccinated was primarily due to employers’ refusal. Sandigan’s approach has, therefore, included promoting the fact that vaccination of domestic workers does not come at any cost for employers and that protecting the health of domestic workers by way of vaccination also benefits the health of employers and their households.

Brazil

In the Latin American region, the Movimento Nacional de Catadores de Materiais Recicláveis (MNCR), a 200,000-member-strong waste picker organization in Brazil, capitalized on the announcement that waste pickers were to be included as frontline workers eligible for priority access to vaccination. The organization intensively promoted vaccination among its members, which resulted in the majority of waste pickers in the city of Brasília being vaccinated within the space of only two days. MNCR has also continued to support their members in receiving booster vaccinations.

Argentina

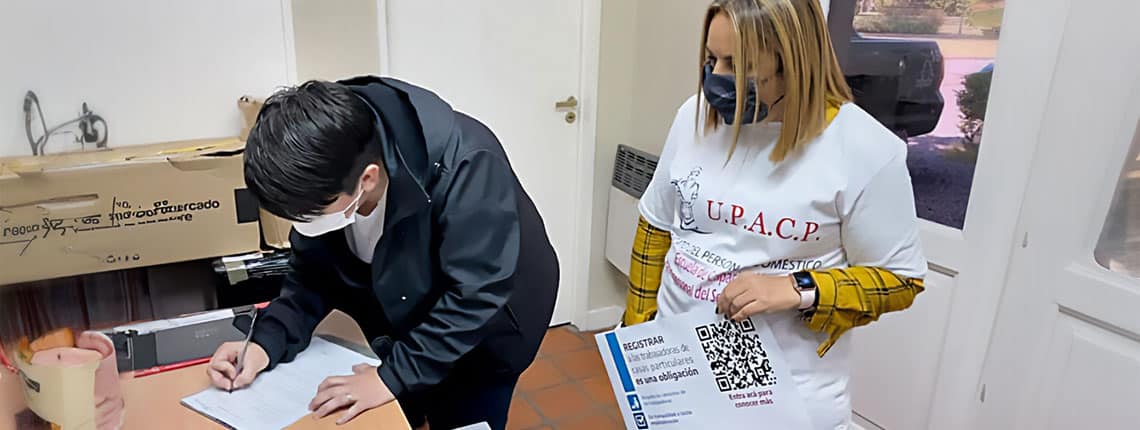

In Argentina, the Unión de Trabajadores y Trabajadoras de la Economía Popular (UTEP) assisted workers in a range of occupations within the informal economy to register for vaccination. They deployed health promoters to low-income neighbourhoods to help people navigate the digital registration system. While domestic workers weren’t included as a priority group for vaccination in Argentina, the sharing of information about the vaccine and how to get vaccinated by the Unión del Personal Auxiliar de Casas Particulares (UPACP) successfully increased workers’ access. In the words of Carmen Britez, Secretary of Organization and Acts of the UPACP and President of the International Domestic Workers’ Federation, their work on vaccination “was well worth it”.