COVID-19 and Delhi’s Waste Pickers

By: Avi Majithia

July 2020

Jagruti Devi is a waste picker and lives in the slums of Rangpuri Pahadi in Delhi. Her husband collects waste in the mornings and sells vegetables on a pushcart in the evenings, while Jagruti Devi segregates waste at home. Since the COVID-19 pandemic hit and the lockdown was put in place, her husband hasn’t been able to go out to collect waste or to sell vegetables.

“We haven’t been able to work since March. We have no savings left. If we can’t go back to work, I don’t know how we are supposed to survive,” Jagruti says.

The lack of income during the lockdown manifested in the acute hunger that most of the urban poor faced in Delhi. When asked about food, Jagruti Devi showed her indomitable spirit, in the face of such stark difficulties.

“They distributed rations in our colony. I had to go stand in line for three hours, but I was able to get some rations. It didn’t last for very long because I also shared it with my neighbour. She’s old and she can’t go get anything for herself. I had to help her too.”

Jagruti Devi is one of the many informal waste pickers who make up 2-3 lakh of the city’s population and are instrumental in the city’s waste management system, as well as in providing environmental and public health benefits. A single person on foot is estimated to collect, sort and transport 10-15 kilograms of waste a day in Delhi, while those with tricycle carts can collect 50 kilograms a day.

Informal waste pickers currently recycle 20 per cent of the total waste generated in Delhi, approximately 2500 tonnes per day (CSE, 2017; Chintan, 2018). Through recycling 80 per cent of total waste, waste pickers provide innumerable benefits to the city, such as lowering pressure on landfills, reducing the quantity of waste for incineration and preventing waste from collecting in streets and near homes, thus maintaining public health.

In current times, waste pickers are facing immense health and economic threats in the city. Informal waste pickers are often the most vulnerable of the urban poor. Largely migrants belonging to lower castes, they live in slums with very poor infrastructure for services. Since the pandemic hit, most haven’t been able to go out and collect waste. The majority of their earnings come from selling dry waste and recyclables to scrap dealers but due to the ongoing crisis in the country, these junk shops have also shut down. The lack of work has sent many into a situation of absolute hunger and deprivation. When they are able to step out of their homes for work, they face police harassment.

A recent study of women waste pickers during lockdown in Delhi, shows that the majority of respondents faced difficulties in going out to collect waste because police are patrolling the streets and they lack protective equipment. 68 per cent of those interviewed, reported that the shutting down of godowns and junk shops have made sorting and selling recyclables nearly impossible. The study also reports that waste pickers faced a severe shortage of food and obstacles for accessing essential medicines and healthcare services. The severe impact of the pandemic on their life and livelihood means that, wherever possible, waste pickers are stepping out for work, irrespective of protections for their own safety and health.

Post-lockdown, many waste pickers have started going to work, but now they seem to be confronting another danger: the threat of infection without any protective equipment.

Waste pickers are on the frontline of defence against the spread of COVID-19, as they are managing the city’s waste while exposing themselves to disease and infection in the process.

As waste pickers resume work, the city needs to help protect them and their livelihoods:

- First, the government must acknowledge their role as essential and include them in the protection and insurance schemes for frontline workers. Their livelihood needs to be promoted and their health needs protection.

- The government should work to ensure provision of protective equipment like masks, gloves and boots, as well as sanitation products (soap and sanitisers).

- Living in some of the poorest slums of Delhi, waste pickers also need support for income and food security. An immediate cash transfer will help waste pickers recover from the economic impact of the lockdown on their lives.

- Finally, the government should work to ensure waste pickers have access to regular health check-ups and essential medicines.

COVID-19 and Delhi’s Home-based Workers

By: Malavika Narayan

July 2020

Until about four months back, if one were to walk through the small by-lanes of the Savda Ghevra resettlement colony in North-west Delhi, it was common to find women sitting at their doorsteps alone or in groups, assembling toys from sacks of colourful plastic pieces. Others would be deftly cutting out sandal straps from long rubber sheets and bunching them up in sets of a dozen pairs each, while again others would be doing intricate bead work in a manner that seemed almost effortless. With the setting in of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures announced to curb it, this can no longer be seen.

The type of work described above is home-based work, a kind of informal employment that engages a large section of women in many urban poor settlements of Delhi. Home-based workers undertake paid work from within the confines of their own homes or premises. While some of them are self-employed, buy their own raw materials and sell the finished goods to local customers, others are subcontracted by larger firms in domestic and global supply chains.

Home-based workers in Delhi are engaged in a range of trades, from manufacturing to packaging, repair and food-processing. They can be seen doing highly-skilled hand embroidery and embellishment work for large global fashion brands, finishing up products manufactured in small factories, or packaging different kinds of products for sale. They receive this work through middlemen or subcontractors and are mostly paid at piece-rates.

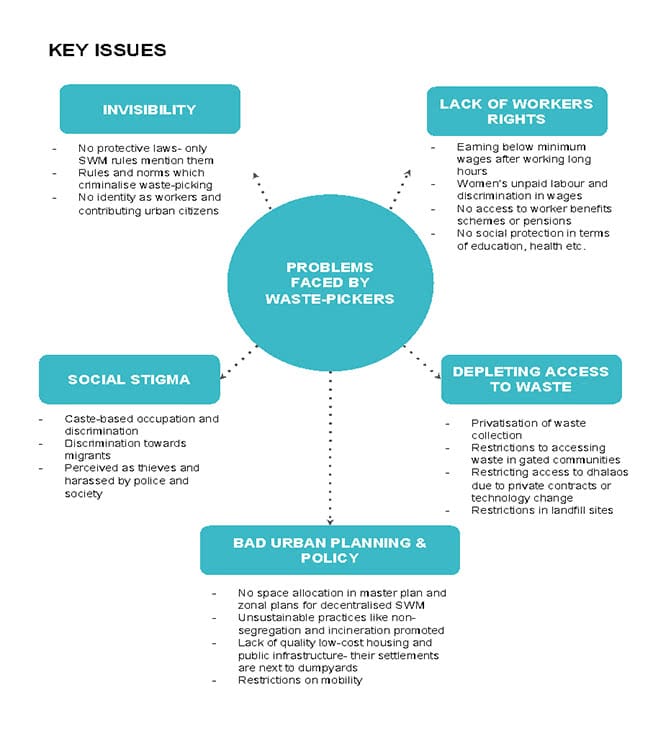

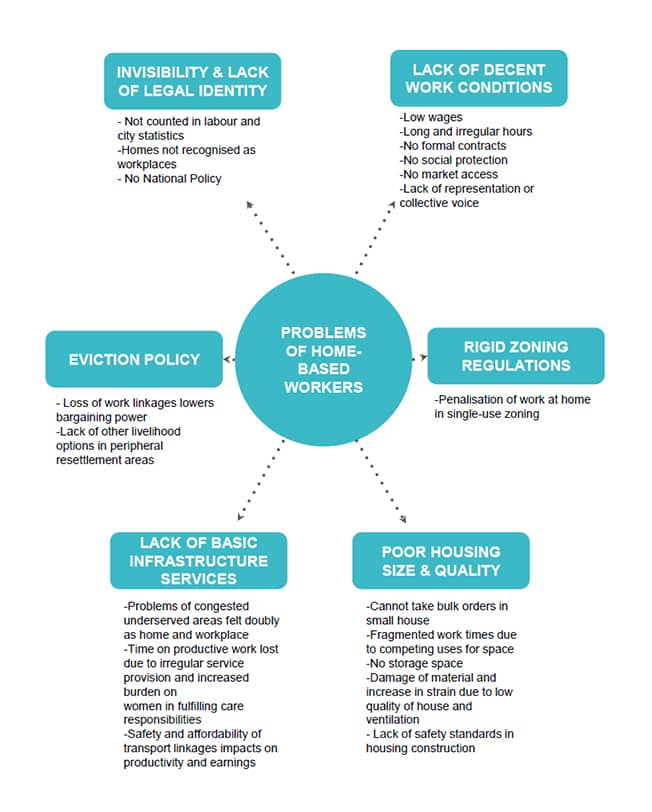

Even though home-based workers work for long hours and contribute significantly to both their households and to their employer’s value chains, they are hardly ever acknowledged. Their work is undervalued as ‘time-pass’ activity and these workers do not get any of the protections or benefits that a worker is entitled to. The following chart maps some of the key issues faced by these home-based workers.

In the past few months, many of these challenges have been exacerbated. There is virtually no work coming into the colony. Many of the factories in the city, from where contractors used to source work, are shut and the middlemen themselves are out of work. Many women workers have unsold inventory and have not been paid for previous orders. Those who are self-employed are also without income, as they cannot meet with customers or go to the markets to procure raw materials. Today, even as the city is slowly opening up, it is still unclear if or when orders for home-based workers will revive.

The loss of income is causing severe hardship. Many of these workers have been unable to meet even their basic needs for food or milk. While a small number found an alternative way to earn an income —making masks, for example— or have another breadwinner in the house, others are in extreme distress. All or most of their savings have been used up and many workers have had to either sell their assets or borrow from moneylenders at high interest rates. The risks of contracting COVID-19 are still very high, which prevents workers from going out and looking for work.

Most home-based workers are women who face additional demands on their time for household chores, cooking and child care during the pandemic. And since schools and child care centres are closed, that work is without respite. The need to increase the visibility and recognition of home-based work is a longstanding demand and is even more urgent now:

- In the short term, targeted support for recovery of livelihood is a must. Many home-based workers are adept at tailoring work and governments need to engage them to manufacture masks and other essential protective equipment for which demand is now high, so that their skills can help others while enabling women workers to earn much-needed income for their struggling families.

- Organizations of home-based workers are also demanding that brands extend a one-time Supply-chain Relief Contribution (SRC) to all workers in their supply chains, during the COVID-19 crisis.

- In the longer term, home-based workers should be brought under the Minimum Wages Schedule and receive extended social security and other worker benefits. All actors along the supply chain, from brands and firms right down to the contractor who finally employs home-based workers, have to be made accountable to ensure decent working conditions as well as occupational safety and health.

In this moment of blurred boundaries between home and work in the face of a worldwide public health crisis, let us remember and stand by those workers who have always been working from within their own homes as an unrecognized but integral part of our economic system.

COVID-19 and Delhi’s Domestic Workers

Malavika Narayan

July

For the last 20 years, A’s day began when it was still dark outside. But, by the time she was done with all the household chores such as cleaning and cooking for the family of five, she would often already be running late. Leaving home at a quick run to the nearby bus stop, she would then travel for an hour and a half in a crowded bus to the elite neighbourhood, where she worked as a domestic worker in three households. When she got back home, there was hardly enough time to get dinner together before calling it a day. This was her routine six days a week throughout the year, until the COVID-19 outbreak in March this year. However, the respite was not a welcome one as it came with worries about being paid her dues and the stress of guarding against a disease which seemed to be all around.

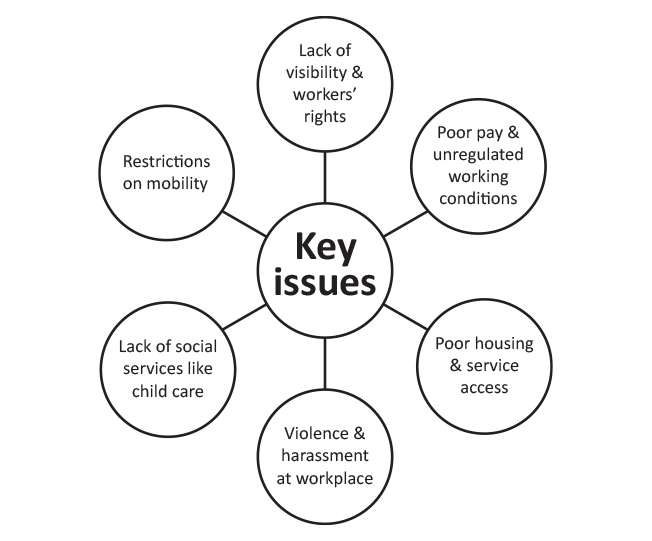

Domestic workers like A constitute around 13 per cent of women’s employment in Delhi, counting up to 1.18 lakh of the 2.23 lakh domestic workers in the city. According to the ILO, it is the fastest growing sector for women in urban India. While some definitions include tasks like gardening and driving which are done by men, domestic work is generally understood to be a predominantly female occupation. As many of the tasks performed, like cooking, cleaning, child care and geriatric care, are seen as an extension of the unpaid care work that women do in their own homes, domestic workers are highly undervalued and underpaid. Moreover, since the work is performed in the private homes of employers, domestic work remains invisible and unregulated, and does not come under the purview of most labour laws.

While some are live-in workers who stay with the employing household, others are live-out workers who may work in one or more households while going back to their own homes at the end of a working day. The earnings vary depending on whether they are calculated per task or on an hourly or monthly basis and they can even depend on the location or other factors. However they are calculated, they largely remain below the minimum wages stipulated by the government. Many are inter-state migrants and belong to particular backward castes.

Unlike many other informal workers, domestic workers have a clear relationship with their employers. Hence, in the context of the lockdown announced to curb COVID-19, public advisories were put out urging employers to pay their domestic workers for the period that they were unable to do so because of the movement restrictions imposed. However, as this was not enforceable in any manner, the vast majority of workers received only partial payment for the month of March and no wages for the subsequent two months, when lockdown was extended. Instead, they had to rely on emergency provisions from the government or civil society for food. Surveys found that, because income from women’s domestic work is regular and often accounts for around 50 per cent of the household income, many families were pushed into exhausting all their savings and became indebted.

Apart from non-payment of dues, many domestic workers expressed shock about the callousness with which employers, for whom they had cared for many years, abandoned them in a time of distress. Many stopped taking workers’ calls and did not reassure them that they would be taken back when work could be resumed. While some workers were asked to move into their employer’s house, many were unable to do so. It is unclear whether those who did were paid higher wages to account for the longer hours of work they were now putting in or whether live-in workers got adequately compensated for the increased work burden due to all members of the employers’ family being at home the entire day.

Eventually, as cities began to open up, domestic workers were faced with a host of fresh problems. In spite of government mandates, many housing societies and apartment complexes were not willing to allow access to domestic workers, due to the prejudiced notions about the poor as ‘dirty’ and ‘carriers of disease’. In places where they were let in, there were reports of discriminatory practices, like not being allowed to use the lifts, common areas and even being subject to dehumanising ordeals of being ‘disinfected’. Being involved in cleaning work and even shopping for their employers, these workers are at higher risk of infection. As public transport is still closed in many cities, workers are now either having to walk long distances or rely on costlier informal transport options like rickshaws, which are also crowded and dangerous.

Urgent action is required to mitigate the many challenges faced by domestic workers.

- First and foremost, domestic workers have to be recognised as workers and their work has to be brought under the ambit of labour laws and regulations guaranteeing living wages and decent work conditions.

- Governments have to work with individual employers and stakeholders like Resident Welfare Associations (RWA) to prevent stigma and discrimination against workers and to promote their welfare. There is an urgent need for a massive public campaign to champion domestic workers’ rights with collective bodies of employers like RWAs.

- Collective identity and mobilisation of workers should be promoted to enable workers to raise their needs and demands, and existing strong collectives of domestic workers have to be included as key partners at the table to advocate for their rights.

- City policies should recognise the essential services and contribution of domestic workers, and support them through provision of quality housing, basic services, child care, good public transport etc.

- As domestic workers are providing essential services which support the fight against COVID-19, they should be protected through necessary equipment, health care and insurance.

COVID-19 and Delhi’s Street Vendors

Avi Majithia

July 2020

On Wednesdays, pre-Covid, the by-lanes of my colony started looking busy around 3 p.m. Small trucks and vans would come in, carrying produce, tables, and lights. Very soon, a market took shape, selling vegetables, fruits, household goods and snacks for vendors and customers alike. There was order to the controlled chaos, keeping in mind the clientele that would begin to start drifting in, as the day started to cool. The market thrived till late into the night, with many consumers buying their daily needs for the week. This is the experience of just one of the many weekly markets that are integral to the fabric of life in the city. From the smallest of communities to the poshest housing localities, a weekly neighbourhood market to buy fresh fruit and vegetables is a unifying experience in Delhi.

This commonplace experience changed back in March when the country went into lockdown with just four hours’ notice. There was to be no movement on the streets and for lakhs of street vendors, their only source of livelihood disappeared overnight.

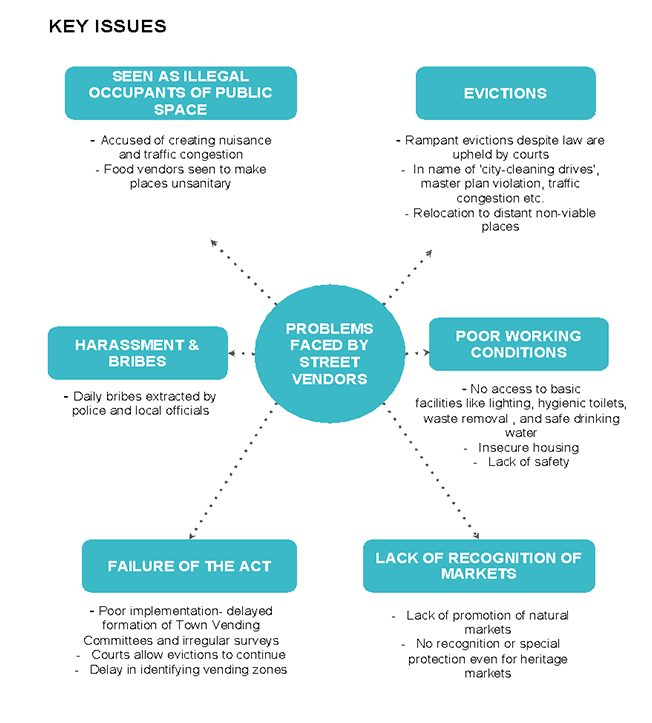

Street vendors constitute an integral and legitimate part of the urban retail trade and distribution system for daily necessities of the general public. They represent 4 per cent of the urban workforce across India and play a variety of roles in city life. There are close to 300,000 street vendors in Delhi, but the Municipal Corporation of Delhi officially shows figures of “legal” vendors in roughly around 125,000 of which around 30 per cent are women.

Vending provides a source of low-paying but steady employment to many migrants and urban poor, while simultaneously making city life affordable for others: vendors provide a key link in the distribution system of food and other critical goods at affordable prices. Street vendors are the main source of food security for many households. Street vendors are also integral to the cultural heritage and ethos of cities in India. The street vending economy in India has an approximate turnover of Rs 80 crore a day.

The COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing lockdown has affected vendors badly. The disrupted networks of distribution and consumption have had a devastating effect. For example, during the lockdown, there was acute shortage of vegetables, mutton, eggs and other food items. Access to produce was halted due to lack of available transportation and the sealing of borders between cities. Even where vendors were able to access wholesale goods, there were little to no earning opportunities –with the growing fear around COVID-19, buyers were not stepping out of their homes and, therefore, vendors had very few customers.

A study of women vendors in Delhi found that most have completely lost their livelihoods, with 97.14 per cent of the respondents reporting that they had been adversely affected by the lockdown. 65 per cent of respondents also said that they were dependent on personal savings to help them sustain the loss of income.

In addition, despite the essential goods they provide, getting back to work comes with risks for vendors. There have now been many reported instances of harassment at the hands of the police, including destruction of goods and property.

Street vendors are one of the worker groups who have benefitted from a government scheme to soften the blow landed by the lockdown due to COVID-19. In May, the Central Government announced a special credit facility of Rs. 5,000 crore for street vendors, as part of the Atma Nirbhar Bharat Abhiyan. Under the scheme, a vendor is eligible for up to Rs. 10,000 as initial working capital. However, activists and workers alike have opined that the credit loan scheme is not the best medium to provide benefits to vendors, for whom a direct cash transfer would have been more appropriate.

As the city returns to some measure of normalcy, vendors need to be supported to resume work, including being able to implement the safety measures needed to work during a pandemic. The Delhi government recently announced that vendors would be able to resume work, keeping in mind social distancing and other precautionary measures. At the same time, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) has recently announced a consultation for planning pedestrian-friendly markets. Now is the time to capitalise on the government’s momentum and enable vendors to participate in the creation of vending zones and markets that work better for them, with the necessary planning for social distancing and hygiene maintenance.

Advocates have to now be proactive about proposing innovative market design and working with the authorities to ensure safety for vendors. The government needs to take steps for the provision of running water and soap/sanitisers for street vendors at their place of work. Additionally, vendor organisations should work with food safety authorities in the country to train vendors (especially cooked food vendors) to maintain hygiene while working. The Delhi government, which is taking steps to survey street vendors, should work with vendor groups to ensure that a maximum number of street vendors can be included in the survey process, even if they are unable to resume work currently.