Who Are Street Vendors and Market Traders?Street vendors and market traders offer easy and affordable access to a wide range of goods and services in public spaces.

They sell everything from fresh produce to prepared foods, from garments, cosmetics and crafts to mobile phone airtime, and provide services such as haircutting and computer repairs.

Research shows vendors make a critical contribution to the food security of urban residents, especially to low-income urban dwellers. Despite their contributions, street vendors and market traders face many challenges and are often hurt rather than helped by urban policies and practices.

Featured ResourceStreet Vendors and Public Space: Essential Insights on Key Trends and Solutions

Through photographs and text, this e-book shows the important role street vendors play in cities, the challenges they face and solutions that can make cities more vibrant, secure and affordable for all.

Defining Street Vendors & Market Traders

Street vendors sell goods and offer services in broadly defined public spaces, such as streets, parks and open spaces near transport hubs and construction sites. Market traders sell goods and provide services in stalls or built markets on publicly or privately owned land.

Challenges & AdvancesStatistics on Street Vendors & Market Traders

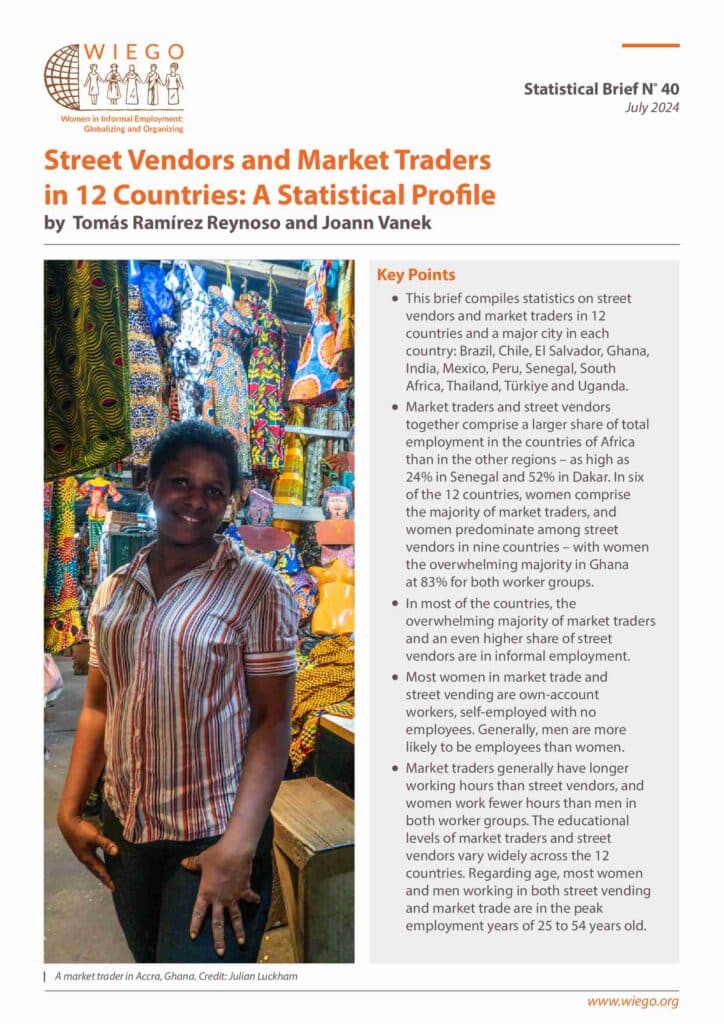

Street vendors and market traders are a large workforce in many cities, yet it is difficult to accurately estimate their numbers. Data to identify these workers are often collected in labour force surveys but are generally not available in the standard tabulations of national statistical offices.

The WIEGO Statistics Programme publishes data based on official statistics on both street vendors and market traders. In 2012, WIEGO published data on street trade in 11 cities in 10 countries. A 2024 publication, Street Vendors and Market Traders in 12 Countries: A Statistical Profile, compiles statistics on the numbers and characteristics of street vendors and market traders based on the WIEGO Statistical Brief series and on recent data for Brazil, Chile, El Salvador, Ghana, India, Mexico, Peru, Senegal, South Africa, Thailand, Türkiye and Uganda. The statistics reported below are based on this brief.

-

24%

of people who work in Senegal work as street vendors and market traders.

-

68%

of street vendors in Peru are women.

-

86%

of women working as market traders in Ghana are own-account workers (self-employed with no employees).

Additional Statistics on Street Vendors and Market Traders

-

Street vendors and market traders together comprise a large share of total employment in many countries, especially in Africa. Street vendors and market traders as a percentage of total employment in select countries (survey date in parenthesis):

- Ghana (2015): 21%

- Senegal (2019): 24%

- El Salvador (2021): 10%

- Peru (2019): 8%

- India (2022/2023): 3% (street vendors only)

- Thailand (2017): 4.5%

-

In many countries, street vending and market trading are dominated by women. Women are the majority of street vendors in 9 of the 12 countries.

- Ghana (2015): 83%

- Peru (2019): 68%

- El Salvador (2021): 67%

- South Africa (2023): 62%

- Senegal (2019): 57%

- Mexico (2023): 56%

- Uganda (2021): 54 %

- Brazil (2020) and Thailand (2017): 53%

The countries where men predominate are Chile (55%) and Türkiye (85%).

Women comprise the majority of market traders in Ghana, Uganda, Thailand, El Salvador, Mexico and Peru. In two of these countries, women are the overwhelming majority of market traders: Ghana, where women comprise 83%, and El Salvador 72%.

Learn more -

Most women in market trade and street vending are in more vulnerable employment as own-account workers, that is, self-employed with no employees.

- The percentages of women in own-account employment among market traders nationally range from 50% in Peru to 86% in Ghana.

- The percentages of own-account workers among women in street vending are even higher than in market trade, ranging from 72% to 89% across the countries, except in Türkiye and India.

- Generally, men in market trade and street vending are more likely than women to be employees, with the exception of market traders in Brazil (21% of women and 15% of men) and Chile (7% of women and 4% of men).

- Further, in India, street vending and market trade taken together stand out with 76% of women working as employees in comparison to 27% of men.

Street Vendors’ Contributions

Statistics consistently show that street vending and market trading play an important role in generating employment, especially for women, and are key to sustaining families and to the food security of poorer urban residents. These activities also contribute to:

- Job creation: In addition to creating jobs for themselves, traders generate jobs for porters, security guards, transport operators, storage providers, and others.

- The economy: Many vendors source their goods from the formal economy. They often pay value-added tax which, unlike their formal counterparts, they cannot claim back.

- Tax base: Street vendors commonly pay a variety of taxes, fees and levies that contribute to local and national government revenue.

- Urban management: Many vendors try to keep the streets clean and safe for their customers.

- Street life, heritage and tourism: Street trade adds vibrancy to urban life and in many places is considered a cornerstone of historical and cultural heritage.

Driving Forces & Working Conditions

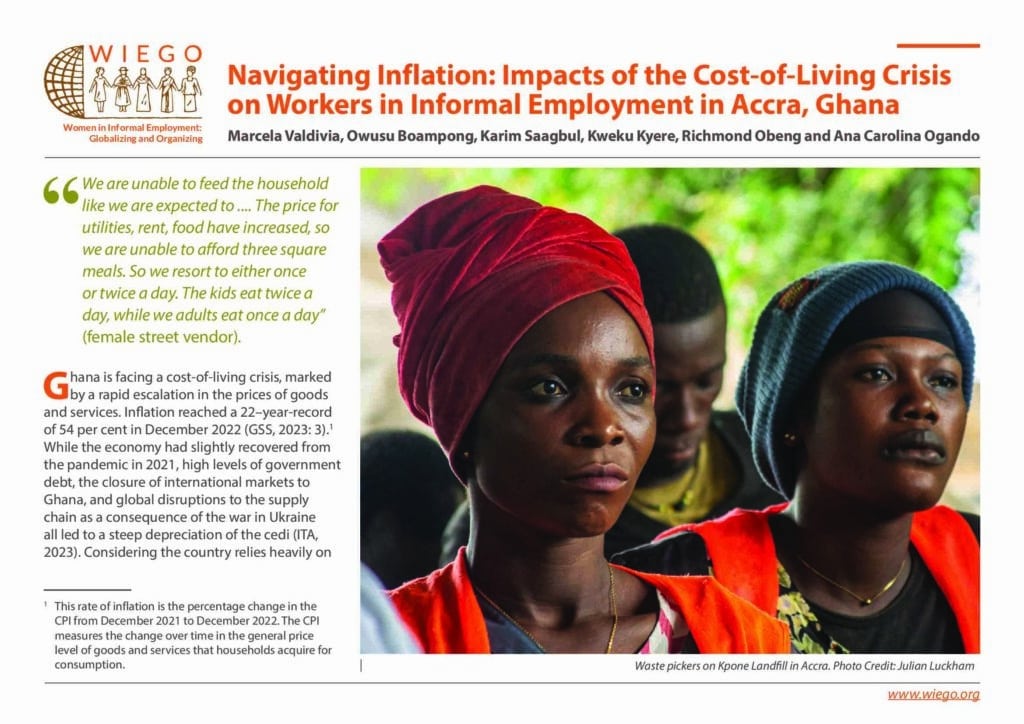

Low barriers to entry, limited start-up costs and flexible hours are some of the factors that draw street vendors to the occupation. Many people, especially migrants, enter street vending because they cannot find a job in the formal economy.

Street trade can offer a viable livelihood, but earnings are often low and risks are high. Having an insecure place of work with little infrastructure is a significant problem for those who work in the streets. Theft or damage to stock and lack of storage are common problems.

Urban policies are frequently punitive because street vending is viewed as antithetical to ‘modern’, ‘hygienic’ and ‘investor-friendly’ cities. By-laws governing street vending often criminalize vendors. Cities that do issue licences frequently have limits on numbers.

-

The COVID-19 crisis study revealed how measures to prevent the spread of the virus severely impacted vendors’ ability to earn a livelihood. Vendors were interviewed in nine cities.

- In April 2020, at the height of restrictions in most cities, 81% of vendors were unable to work and median earnings were zero.

- In mid-2021, while 80% of vendors were back at work, they had recovered only 60% of their pre-pandemic earnings.

COVID-19 was not the first crisis to hit street vendors hard. WIEGO’s Global Economic Crisis Study showed how in 2009 street vendors experienced a drop in consumer demand and an increase in competition as the newly unemployed turned to vending for income. In 2010, most vendors had not recovered and many had to raise prices due to the higher cost of goods and increased competition from large retailers.

-

Working outdoors in urban environments, street vendors and their goods are exposed to strong sun, heavy rains and extreme heat or cold; all of which are becoming more acute with climate change. Many do not have shelter, access to clean and potable water, sanitation or toilets near their workplace –- with major implications for street vendors’ health, well-being and livelihoods.

Street vendors face a wide variety of other occupational hazards. Many lift and haul heavy loads of goods to and from their point of sale. Market vendors are exposed to physical risk due to a lack of fire-safety equipment, and street vendors are exposed to injury from the improper regulation of traffic in commercial areas.

Insufficient waste removal and sanitation services results in unhygienic market conditions and undermines vendors’ sales, as well as their health and that of their customers and communities.

-

Despite street vendor and market trader contributions, punitive urban policies and practices are pervasive, with street vendors frequently being evicted from public space. This is often done in the name of ‘world class’, ‘orderly’ and ‘modern’ cities. Local laws often criminalize vending, and/or zoning prohibits these practices. Where traders are licensed there are frequently restricted numbers. Urban design tends not to accommodate street vending.

Policies & Programmes

Inclusive approaches to street vending and market trading are possible. Working alongside street vendor organizations, WIEGO provides evidence of contributions, as well as technical guidelines and policy opportunities, to strengthen their hand in negotiations, especially with local authorities.

-

WIEGO’s Urban Policy Programme and Focal Cities support models of inclusive planning and design, for example, Asiye eTafuleni’s work in Warwick Junction, Durban, and Focal Cities’ work in Mexico City. In Delhi, the implementation of India’s Street Vendor Act is monitored. We have developed public space guidelines for workers, local government officials and policymakers.

-

Street vendor livelihoods are defined by regulations, by-laws and city ordinances that give local authorities powers to govern access to the public space and resources vendors rely on.

Challenges workers face often result from how those powers are designated, interpreted and exercised. The principles of administrative justice regulate the actions of government officials – they must be lawful, reasonable and procedurally fair. This makes administrative justice a tool workers can leverage to contest actions that impede their work, and push for inclusive decision-making that, ultimately, changes laws.

The WIEGO Law Programme seeks to understand law’s impact on livelihoods in urban space in order to reconfigure urban governance relationships to better advance the human rights and labour rights of workers in informal employment. Projects include Organizing through Administrative Justice and R204 and the book Mapping Legalities: Urbanisation, Law and Informal Work.

-

Like all workers, street vendors require comprehensive social protection to ensure their livelihoods and well-being are protected.

Street vendors face challenges in accessing social protection similar to those of other groups of largely self-employed workers in the informal economy, such as home-based workers and waste pickers. Often, work-related social protection schemes are not well designed for poorer self-employed workers, who may face legal exclusions from such schemes. Affordability and timing of contributions are among barriers to workers’ participation in social protection schemes, which often face administrative challenges.

The WIEGO Social Protection Programme seeks to explore how work-related social protection schemes can be made more accessible for self-employed workers in the informal economy, including street vendors. Examples of our work include a study conducted with the ILO on the innovative Monotax scheme in Uruguay, and a policy brief making recommendations on the reform of social protection systems in Lao PDR.

Organization & Voice

Membership-based organizations help street vendors navigate their relationship with the authorities, build solidarity and solve problems with other vendors. Several have developed innovative ways to work with cities to keep the streets clean and safe while gaining a secure livelihood for vendors. Key demands of organized street vendors and market traders include the provision of infrastructure – such as designated and appropriately designed trading and storage space, toilets, and access to affordable water and electricity – social protection coverage, an end to harmful city regulations and practices, and inclusion in all levels of decision-making on matters that affect them.

A strategy pursued by street and market vendor organizations to achieve these demands is to insist that local authorities recognize them as bargaining partners and agree on local negotiation forums. WIEGO and StreetNet International produced a handbook on Collective Negotiations for Informal Workers as part of the Organizing in the Informal Economy: Resource Books for Organizers Series.

WIEGO works closely with StreetNet International – formed with WIEGO support in 2002 – as a means of amplifying the voice of street vendors and market traders internationally.

More Occupational Groups

-

Garment Workers

Learn More -

Home-Based Workers

Learn More -

Domestic Workers

Learn More -

Waste Pickers

Learn More