Valdete Roza is a Brazilian waste picker and leader in her cooperative who is pioneering gender discussions with her colleagues across her city and country.

Like working women across the world, Valdete Roza hurriedly squeezes in a host of domestic activities — hanging newly washed clothes, making breakfast and prepping ingredients for the evening dinner — before heading out of the house to earn income to help support her family.

"We need to care for women because she is the one caring for people. Through this personal growth she will have economic growth.”

Balancing these responsibilities is challenging, especially when her work as a waste picker is physically demanding, and as treasurer of her cooperative, Atlimarjom, she is constantly strategizing how to better her organization and its 21 members, 12 of whom are women. She uses her leadership position within the cooperative to support her hard-working women colleagues. She wants them to recognize their own dignity and self worth, which she says are game-changing realizations in promoting women’s earning-power.

This validation of women waste pickers’ own strength and self worth is essential, she says, “so that they can grow as people, as humans, inside their cooperatives. It’s not just the material [aspect]. We need to care for women because she is the one caring for people. Through this personal growth she will have economic growth.”

Read more about how waste pickers are helping to solve the global ocean plastics waste crisis.

Dignity for a “dirty” job

Valdete’s point about strengthening the dignity and self worth of women waste pickers is especially important. These workers are among the poorest urban residents and are often undervalued or seen by the public as “dirty”, despite their heroic efforts to keep cities clean. These external perceptions can easily be internalized, and make it challenging for women to recognize their own multifaceted strengths.

Valdete knows these battles all too well. She spends 10 hours a day sorting through piles of the city’s discards to give them value in society again — a special ability that seems to mark all Valdete does.

“So many of the men would say, ‘Ah Valdete, she’s not going to stay here, she doesn’t know how to handle all the materials,’”

But as a women, work is never just about being solely on the job. While doing her backbreaking labour, she hears the chatter of women around her: updates on an ailing parent, evenings spent with children on homework, new recipes being tested out, and the birth of a newborn — all while keeping an eye on the oscillating prices for recyclable materials and making a mental note to organize members’ monthly payments.

Read about waste pickers in our Informal Economy Monitoring Study (IEMS).

Facing gender challenges

Although Valdete has mastered her understanding of waste over the years, she first had to overcome the doubts of those already in the business, especially among the men. When she got started in waste picking, her male counterparts would make comments about her lack of knowledge. “So many of the men would say, ‘Ah Valdete, she’s not going to stay here, she doesn’t know how to handle all the materials,’” she recalls.

Today, she swiftly sorts materials of every kind, not just in large categories, such as metals, plastics and glass, but into micro separations depending on the varying value on the recyclable market.

Many of the women at the cooperative are the breadwinners at home.

Despite her hard work and increased knowledge, she has faced many gender discriminations. As she gained her leadership position within the cooperative, she recalls a man showing up to work and saying he wasn’t going to take orders from a woman. “I said: ‘Listen, you are going to leave here today. Look around — do you see all the women working here? Women are the leading this here; there are no men directing this.’”

Valdete says she is surrounded by women who are there for a reason: they need the income. Many of the women at the cooperative are the breadwinners at home, ensuring their families stay afloat. "They're here to eat.They don’t want their pantry empty,” says Valdete. “They want their kids to have school supplies. It’s a huge struggle. It's a constant struggle. It's a struggle for all women."

But Valdete learned along the way that even with these sacrifices that women make, they still need to focus on their own sense of worth and self respect.

Read more about women’s economic empowerment.

Creating spaces for leadership for each other

With her own growth, Valdete now has made it her mission to extend that empowerment on to women waste pickers in her city and across Brazil. She wants them to see their validity within their home, at their workplace and in society.

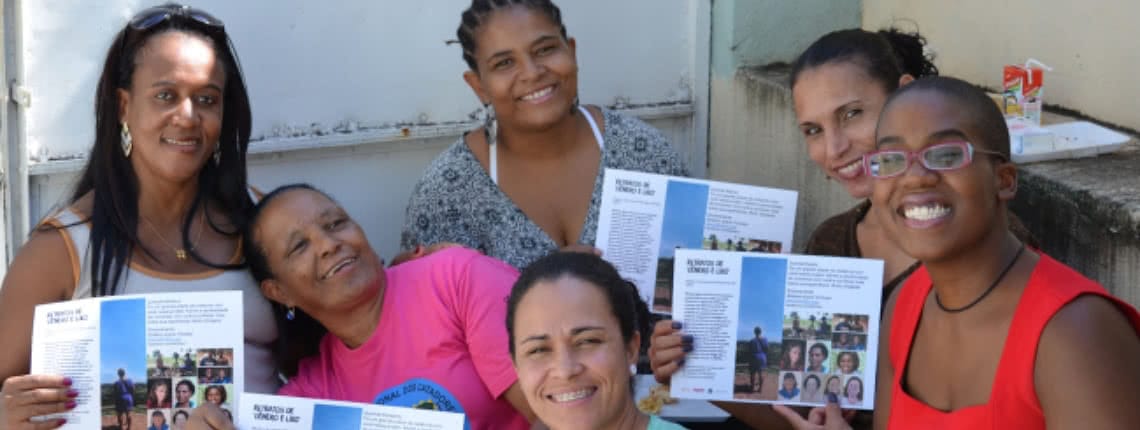

In her cooperative and with the National Waste Picker’s Movement in Brazil (MNCR), she has asked waste picker cooperative leaders near and far — both men and women — to start discussing gender dynamics. As the co-coordinator of the Gender and Waste Project, a participatory action research project carried out with WIEGO between 2012-2015 with 67 women from 41 waste picker cooperatives in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, she worked hard to mobilize participation to make change happen.

She has asked waste picker cooperative leaders near and far — both men and women — to start discussing gender dynamics.

The pioneering activities brought women waste pickers together — often for the first time — to discuss the physical and emotional effects of working in the waste sector; gender-based forms of violence, ranging from bullying from colleagues to violence at home; and the need to have their voices heard in high-level waste management decision-making processes. For the first time, these women were given a safe space to be heard on issues that often go untalked about.

She recalls one woman attendee who brought up how girls are raised differently from boys — how girls “have to behave well” and “play with certain things”. Valdete hadn’t thought much about the origins of the discrimination they all face today. “When we meet it helps, because I hadn’t thought of this. It’s like, ‘Oh yeah, I hadn’t thought of that, but yeah’. It’s like a discovery when we have gender discussions.”

“It’s an awakening when you hear about another woman who was able to achieve something. It’s all about strengthening one another,” says Valdete.

Other women shared how they have overcome certain obstacles in their lives. “It’s an awakening when you hear about another woman who was able to achieve something. It’s all about strengthening one another,” says Valdete. “And you start to see the other in a new light. You start to think you are capable.”

Valdete says that listening is actually one of the most powerful parts of the empowerment process, because it “humanizes the work” done by waste pickers, which is often invisible and compounded by racial, ethnic and class discrimination.

Read more about WIEGO’s Gender and Waste Project.

Photo: Vanessa Pillay

Envisioning a more equal world

Valdete is continuing her work to empower women waste pickers. She is focused on bringing more men into gender discussions, since this is an important part of the recognition process. She hopes to do more workshops and strategic planning processes with women leaders in other cooperatives to focus not just on earning power but coaching them into believing in themselves. The rest, she says, will happen from there.

“This is my dream,” she says. “That women get empowered. That this empowerment comes from within and not from outside, so that they really feel it. I want them to raise their heads and say, ‘I’m capable. It’s not because I am black, a woman, a waste picker that I’m nobody. I am capable. I deserve respect, yes I do’”.

This article is part of a month-long series for Women’s Day. Read the opening piece here and the story of a homebased worker in Delhi here.

Feature photo: Ana Carolina Ogando

Para ler este artigo em português, veja aqui.

Related Posts

-

Informal Economy Theme

-

Informal Economy Topic

-

Occupational group

-

Region

-

Language